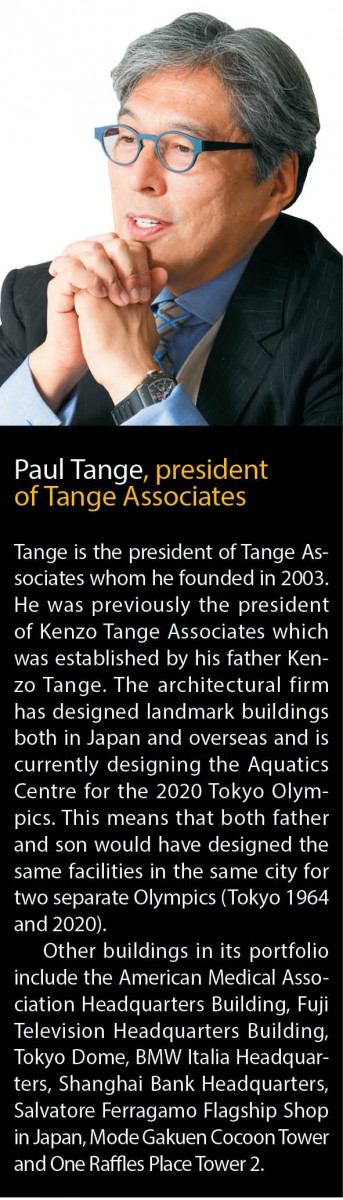

WHEN thinking about architectural design and ecosystems of the future, Japanese architect Paul Tange and his colleagues at Tange Associates constantly challenge themselves with this question —“How do we create a comfortable environment for people?”

Even though technology, particularly green technology, has advanced greatly, more often than not, individual technologies or systems are isolated and are not connected to one another, Tange notes.

For example, governmental evaluations and sustainable building awards do not necessarily create a comfortable environment for people, as they are merely numerical evaluations, he says.

“A certain number of points are given for specific elements. To meet governmental requirements, glass colour may be darker to help reduce heat inside the building. However, dark glass also reduces natural light, which in turn might increase the need for artificial light to brighten the interior. It also distorts the natural colour of the blue sky and green plants, as compared to transparent glass. How does this distorted view of nature impact those inside the building?” he says.

Technological advancement has enabled architects to construct almost any building form or shape, and push the boundaries of creative design. “But are these shapes providing a comfortable space and environment for people?” he says.

Tange believes an architect’s fundamental role is not to obsess with chasing trends but to enrich and strengthen relationships among the city, architecture and people.

Tange believes an architect’s fundamental role is not to obsess with chasing trends but to enrich and strengthen relationships among the city, architecture and people.

Building typologies need to change and constantly be reinvented to adapt to the drastically changing physical and technological environment of cities, says Tange, citing the Mode Gakuen Cocoon Tower in Tokyo as an example of this.

He explains that the firm had to redefine school architecture for the urban setting, with its decision to house three different schools in a 50-storey vertical high-rise building due to land scarcity in Tokyo.

“Urban design or architecture must reflect locality-specific essences, and must take into consideration the country or city’s weather, climate, culture, history, lifestyle and financial condition. Such a design will inevitably be distinct,” he says.

Globalisation, he says, has allowed information sharing to take place easily, with foreign designers bringing great innovation and imagination to the table as they see the local environment from a different perspective.

However, globalisation is a double-edged sword, as it heightens the risk of creating homogenous environments, as architectural designs are adopted wholesale by other countries.

While he is not against importing good design, he stresses that architects need to be sensitive to the local environment, society and culture for which they are designing for, in order for design to be relevant for the people.

Standing the test of time

Being an Olympics host nation is a source of national pride for any country, but Tokyo playing host to the 2020 Olympics holds a personal significance for Tange, as his late father, the renowned Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, had designed the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Summer Olympic Games.

For the upcoming Olympic and Paralympic Games in four years’ time, Tange will be designing the Aquatic Centre and renovating the Yoyogi National Gymnasium. Tange Associates has been involved in the maintenance and upkeep of the latter since its completion in 1964.

“It is obviously a great honour for two generations of Tanges to design for two different Olympics in the same Olympic city. I believe we are the only father and son architects to have had this honour,” he notes.

While the 1964 Olympics was an opportunity for Japan to reintroduce itself on the global stage as a technological innovator after the devastation of World War II, the Japan of today is well known as a leading global power, so how the mature society will view the 2020 Olympics will be very different, he says.

The architectural challenge for Tange remains the same — to ensure the sporting facilities remain relevant to the people of Tokyo even after the Olympics is over.

“What this means is a complex that can accommodate 20,000 spectators during the Olympics being restructured to a 5,000 seating capacity stadium post-Olympics. In both scenarios, the building has to look complete, unlike some other facilities in past Olympics that appear to be temporarily built for the Games,” he says, referring to criticism of major Olympics sporting facilities becoming white elephants around the world.

To achieve this, Tange plans to reduce the post-Olympic seating to a quarter of the Olympic-size capacity, and lowering the roof of the building — a move that not only demonstrates Japanese engineering and technology, but proves practical and cost-effective for future maintenance and running costs, he elaborates.

And he is confident that he can set the bar high for others to follow.

“The Tokyo Olympics will be a good example for future Olympic hosts to see how we address this issue. Asia is leading the world in most aspects. All one needs to do is look around,” he says.

This story first appeared in TheEdgeProperty.com pullout on Oct 7, 2016, which comes with The Edge Financial Daily every Friday. Download TheEdgeProperty.com pullout here for free.