- Unless substantial amendments are made or both legislations are forthwith withdrawn, they risk undermining property rights, community participation, and the democratic governance of the city of KL.

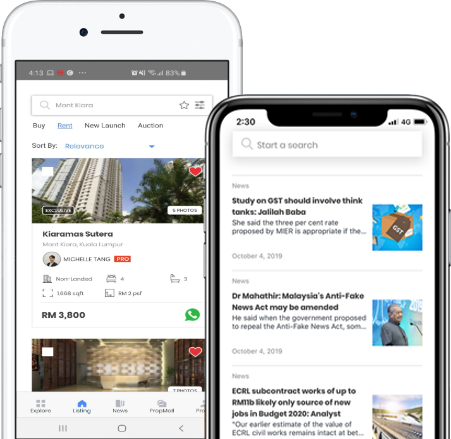

In a move that has raised serious concerns among urban planners, civil society, and concerned citizens, Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) has introduced the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur Planning Rules (FTPR) 2025, which notably removes the requirement for public notification and consultation for certain development projects.

This shift marks a troubling departure from the principle that those who are affected by development—especially residents, business owners, and local communities—should be consulted before any plan is approved. Instead, DBKL’s new framework seems to centralise decision-making and sideline public voices, effectively shutting the public out of decisions that directly affect the liveability, heritage, and sustainability of their neighbourhoods.

This regulatory shift coincides with the fast-tracked Urban Renewal Act (URA)—a proposed federal law that will significantly ease the process for redeveloping old, or alleged dilapidated properties, even without unanimous owner consent.

Together, these two policies could reshape Kuala Lumpur for decades to come. And unless substantial amendments are made or both legislations are forthwith withdrawn, they risk undermining property rights, community participation, and the democratic governance of the city of KL

FTPR 2025: A quiet coup in urban governance

FPTR was gazetted on June 13 and effectively implemented on June 16 within a span of three days. We noted that it was uncharacteristic for DBKL to suddenly become so efficient. It is stipulated under Rule 3, the KL mayor is now merely permitted—not obligated—to consult “any interested party or authority” before granting planning permissions.

The implications are grave. This single change means that residents and stakeholders no longer have a guaranteed legal right to be consulted on developments that affect their neighbourhoods. Whether it's the construction of a high-rise next to a school, or the re-zoning of green spaces for commercial use, the public may never be informed or invited to weigh in.

Seputeh MP Teresa Kok has called this change “a backdoor amendment” and warned that it could open the floodgates to opaque and unaccountable urban planning. Critics argue that such power consolidation erodes transparency and increases the risk of developer-driven planning—all without the community’s consent.

Why public consultation is not optional

Public participation is not a bureaucratic hurdle—it is a democratic necessity. Planning decisions shape the fabric of a city for decades. When done right, consultation ensures that developments are aligned with public interest, are environmentally sustainable, and reflect the values and character of the community.

To exclude the people from this process is to assume that technocrats alone know what is best—a dangerous assumption in a city as diverse and complex as KL.

The absence of mandatory public consultation risks opening the door to opaque decision-making and unchecked development. Projects could proceed despite legitimate concerns over traffic congestion, environmental degradation, loss of green spaces, or the destruction of cultural and historical assets.

It also sets a worrying precedent: if public input can be eliminated so easily, what’s to stop further erosion of transparency?

DBKL’s new rules may also contradict established planning laws and federal commitments to transparent urban governance. It undermines the principles of participatory governance promoted under the National Physical Plan and the Malaysia Urban Rural National Indicators Network for Sustainable Development (MURNInets). MURNInets, under Town and Country Planning Department (PLANMalaysia), is a system for measuring and evaluating the sustainability of a local authority’s area through a set of established urban indicators.

Globally, cities are moving towards more participatory models of governance—not fewer. KL now risks moving in the opposite direction.

URA: A law for renewal or displacement?

If FTPR 2025 limits consultation, the proposed URA limits consent.

Having been tabled in Parliament for its first reading on Aug 21 by the Housing and Local Government Minister Nga Kor Ming, the URA will allow urban redevelopment to proceed even without 100% owners’ consent. For properties over 30 years old, only 75% of owners must agree. For those under 30 years, 80% consent will suffice. Even a simple majority (51%) could override dissenting owners in abandoned or dilapidated properties.

This majoritarian approach is unprecedented in Malaysian land law. Critics, including constitutional scholars, law experts and the National House Buyers Association (HBA), argue that this undermines Article 13 of the Federal Constitution, which guarantees the right to property and stipulates that no person shall be deprived of their property without due process and adequate compensation.

The law also provides limited detail on what “adequate” means—raising fears that market distortions or valuation manipulations could leave displaced owners shortchanged. The diminished consent thresholds and ambiguous compensation mechanisms could violate these protections.

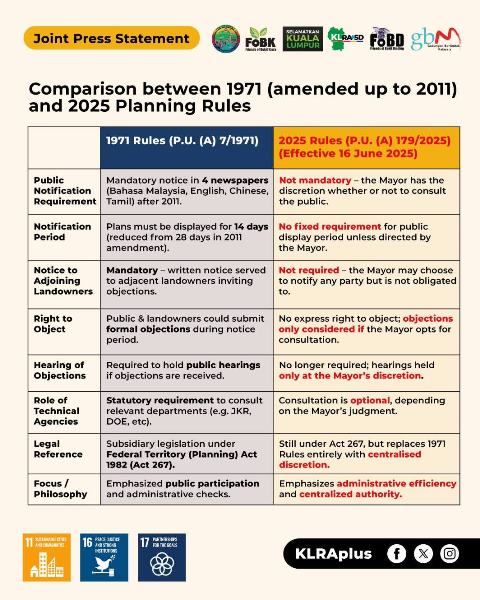

Combined impact: What happens when both are in place?

1. Democratic deficit in urban planning

FTPR 2025 removes mandatory consultation, while URA allows developers to overrule dissenting minorities—together, they dramatically shrink the space for public input and challenge and will “facilitate” private property developers.

2. Heightened risk of rights abuses

Property owners may lose their property—even if they oppose redevelopment—without adequate safeguards or compensation.

3. Privatisation of public assets

FTPR 2025 centralises authority; URA incentivises privatisation—together, public land and commons risk being converted for private profit, reducing equitable urban space.

4. Unchecked executive power and potential cronyism

These laws concentrate power—both legislative and executive—in planning authorities and development decision-makers, potentially fostering corruption or favouritism.

5. Social instability and loss of trust

Communities may feel disenfranchised by the lack of participation, potentially triggering protests, legal challenges, and civil unrest.

6. Legal and constitutional challenges ahead

Both measures potentially violate constitutional protections of property and due process—opening paths to judicial review and litigation under Article 13 of the Federal Constitution.

On their own, each of these legal changes raises concern. But together, they represent a systemic shift in how planning and development will occur in KL. The consequence? Unchecked decision-making power—placed largely in the hands of the mayor, planning authorities, and private developers. There goes the check and balance process of plan making between “top down” and “bottom up” processes.

Urban planning without public input is a house built on sand. The people are not anti-development—it’s pro-democracy, pro-heritage, pro-environment. But, by sidelining mandatory consultation, DBKL risks compromising transparency, equity and the very soul of KL. Democratic planning isn’t an impediment—it’s essential to building a resilient, inclusive, and vibrant city.

The FTPR 2025, in minimising community voice, undermines these goals. As Malaysia’s capital, KL deserves a development that is guided by its people—not conducted behind closed doors and decided by those handful of technocrats. If KL is to remain Malaysia’s vibrant, diverse and equitable city, then its streets and its skyline must be shaped with, not without, its people.

Combined, FTPR 2025 and URA in their current forms, risk entrenching a development regime that prioritises expediency over equity and profit over people. Looks like all the jigsaw puzzles are falling in place for the elites.

This article is written by National House Buyers Association (HBA) honorary secretary-general Datuk Chang Kim Loong.

HBA is a voluntary non-government and not-for-profit organisation manned wholly by volunteers.

HBA can be contacted at:

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.hba.org.my

Tel: +6012 334 5676

The views expressed are the writers’ and do not necessarily reflect EdgeProp’s.

As Penang girds itself towards the last lap of its Penang2030 vision, check out how the residential segment is keeping pace in EdgeProp’s special report: PENANG Investing Towards 2030.