- Napic Property Market Report 2024 shows a strong rebound in both the volume and value of property transactions since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, but increases in property transaction volume and value may not necessarily indicate a good market sentiment.

Figures on gross domestic product (GDP) provide a snapshot of the overall economic activity within a country by aggregating the value of all final goods and services produced. While it is useful in offering a comprehensive measure of the country's economic size and output, GDP has limitations in reflecting the overall wellbeing of a country. GDP growth can be seen as a sign of economic strength, but this growth could be “un-economic”, as human welfare per capita, adjusted for the costs of inequality, environmental damage and other factors that affect welfare, may not have improved throughout the period.

Real GDP, which represents the total value of goods and services produced by an economy adjusted for inflation, tends to rise over time because of increased productivity, technological advancements, and population growth. For example, despite experiencing periods of contraction, based on data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), Malaysia’s real GDP saw significant growth from RM73.7 billion in 1970 to RM1.65 trillion in 2024, alongside its increasing population from 10.45 million in 1970 to 34.1 million in 2024, as well as the evolving economy from one primarily reliant on agriculture to a more diversified, industrialised, and service-based economy (Figure 1).

However, economic growth, as measured by GDP, does not automatically translate to a noticeable improvement in living standards for everyone. It is possible for a country's GDP to increase while many citizens do not feel a better living standard. This disconnection arises as GDP primarily measures the total value of goods and services produced, not necessarily how that wealth is distributed or how it impacts people's daily lives. If a large portion of the increased economic output goes to a small group, many people may not experience the respective economic progress, even with a rising GDP.

In order for an ordinary rakyat to truly feel the growth of the national economy, the growth momentum must be strong enough to create a spillover that covers different economic sectors or layers of society. Just like the economic performance shown during the “golden period” from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, where the growth rate of GDP must, at least, be maintained above 8% for a period of five to 10 years (Figure 2).

Compared to the rapid growth it experienced before 2000, the country’s economy has been softening in the past two decades. Although its GDP growths recorded 8.9% in 2000 and 2022, these growths were primarily due to the low base effect stemming from the 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis and the Movement Control Order (MCO) in 2021, respectively.

In fact, the increased income from the growing economy has been offset by the increased cost of goods and services, leaving people with little or no real increase in purchasing power. This also explains why, despite the government’s recent release of impressive economic data such as GDP growth, foreign direct investment, export trade and stock market performance, indicating continued economic growth and vibrancy, people still feel the opposite, with many even perceiving that the country is entering a recession.

Market realities and data interpretation

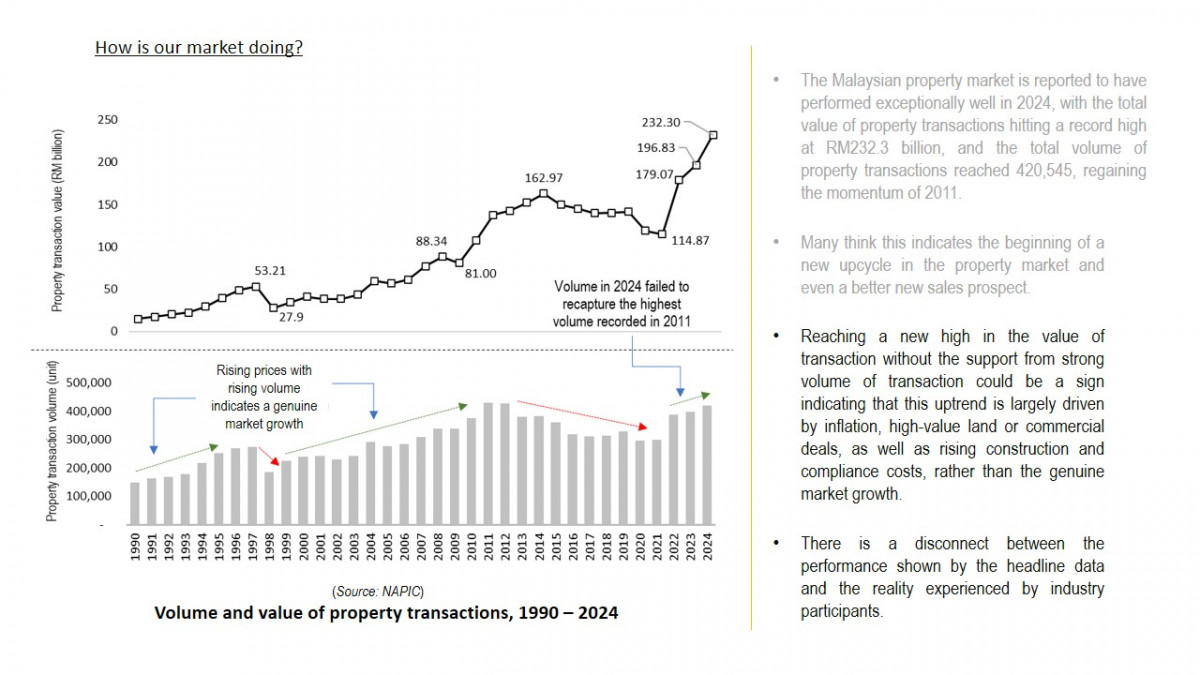

Similarly, there is a disconnect between the performance shown by the headline data and the reality experienced by industry participants. National statistics from the National Property Information Centre (Napic) Property Market Report 2024 show a strong rebound in both the volume and value of property transactions since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic (Figure 3). However, increases in property transaction volume and value may not necessarily indicate a good market sentiment.

Although statistics cite a record-high transaction value of RM232.3 billion in 2024, transaction volume in 2024 (420,545 units) failed to recapture the highest volume (430,400 units) registered in 2011. Reaching a new high in transaction value without the support from strong transaction volume could be a sign indicating that this uptrend is largely driven by inflation, high-value land or commercial deals, as well as rising construction and compliance costs, rather than genuine market growth.

The increase in property transaction value does not always translate to an improved buying sentiment of the property market. This can happen because national level data are summarised or aggregated information, which tends to give a fair coverage of the overall market activity, status, and inventory across the country. While it is essential for long-term market trends and patterns analysis, it is also susceptible to the "ecological fallacy", as conclusions about individuals are drawn from aggregated data, which is unlikely to reflect the operational realities faced by industry players.

To gain a nuanced understanding of the market, which is likely to be influenced by investor confidence, buyer psychology, and overall optimism or pessimism of individual entities that national level data does not always capture; individual level data that offers granular details about property developers’ performance (indicating the supply side) and consumers’ behaviour (indicating the demand side) appears to be more suitable in reflecting the intuitive market health and prospect.

The performance of the market supply side can be examined by studying the profit levels of each listed company over the past decades; and the demand-side sentiment can be obtained by referring to the changing consumer sentiment/confidence index, which is the outcome of surveys on individual households to gauge consumer spending trends and behaviour.

Supply-demand analysis of housing market performance

The supply side of the market was not even better than it was 10 years ago. Following an ever-increasing competitive marketplace, a contraction in developers’ profitability was significant, from an average of 29.5% in 2014 to -22.8% in 2024 (Figure 4).

As high as 53% of the public-listed property development companies achieved a double-digit profitability in 2010. This proportion was even higher in 2014, at 80%; but then declined to 42% in 2024. Meanwhile, the proportion of companies that faced a deficit, which once decreased from a proportion of 9% in 2010 to 5% in 2014, increased to 25% in 2024.

Apparently, the property business operating environment is becoming tougher with rising development costs, sales and service tax (SST)-related expenses, and escalating compliance obligations. Developers are experiencing market polarisation with different buying sentiments at different housing market segments.

For instance, the mampu milik or affordable market segment (houses priced below RM300,000) does not move well as expected, because of issues such as low financial literacy among B40 and low-M40 income-group buyers, especially in relation to loan eligibility, budgeting, and long-term financial planning of individual households. Slow sales are also observed for luxury housing priced above RM1 million, especially in areas like Kuala Lumpur where there is a large supply of high-end houses, putting downward pressure on prices.

On the other hand, properties priced below RM500,000 but with quality and standards better than houses within the affordable segment are performing relatively well, particularly in outer suburban areas; while premium units in prime locations—priced RM500,000 to RM1 million—continue to attract niche investor interest. As such, it is hard to say whether affordable housing targeting the mass market will guarantee good sales, or that there is no demand for high-end products that do not match with people’s income level, because people’s housing affordability depends not only on house prices but also on their spending patterns, which are unlikely to be reflected in the national-level data.

Foo: “Unlike supply-side market performance, which can be tracked through standardised company annual reports, demand-side market performance varies greatly from location to location, making it difficult to discern overall patterns or trends when looking at individual data points.”

Most often, developers rely heavily on their customers/agents/internal sales team’ feedback, competitor benchmarking and mystery shopping, listing portals, and market research/survey/study to tackle buyers’ real intention to purchase in the market. Though this granular data is highly detailed, it is often unstructured and comes from numerous sources, making it difficult to process and validate.

Unlike supply-side market performance, which can be tracked through standardised company annual reports, demand-side market performance varies greatly from location to location, making it difficult to discern overall patterns or trends when looking at individual data points. Without aggregating and standardising the data, it is impossible to draw accurate conclusions about current buying sentiment or market condition.

That being said, data with a sufficiently long record to show consumer spending behaviour in relation to short-term economic conditions, such as Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER)’s Consumer Sentiment Index (CSI), can still provide a proxy indicator of long-term demand-side market performance (Figure 5), especially when comparing the current market with market performance in previous decades.

As shown in Figure 5, a relatively “weaker” outlook of the demand side is painted by CSI, where a greater pessimism is displayed by domestic consumers towards their future finances, incomes, jobs, and inflation levels since 2014. Just like the dampened performance shown in the supply side, CSI has been scoring below 100 for most of the time with an average score of 87.0 throughout the period of 2014–2024; compared to the period before 2014 with an average score of 107.8.

Moving forward, though the property sector is underpinned by the strength of the country's economy, population growth, low interest rates, high employment levels etc, private spending momentum and purchasing sentiment are expected to weaken due to rising living costs.

Besides, a change in the property market and landscape—due to the shifting demographics, growing urban populations, declining household size, continuous inter-state migration of workforce, and highly segmented living standard among the society—also influences the demand-side market performance.

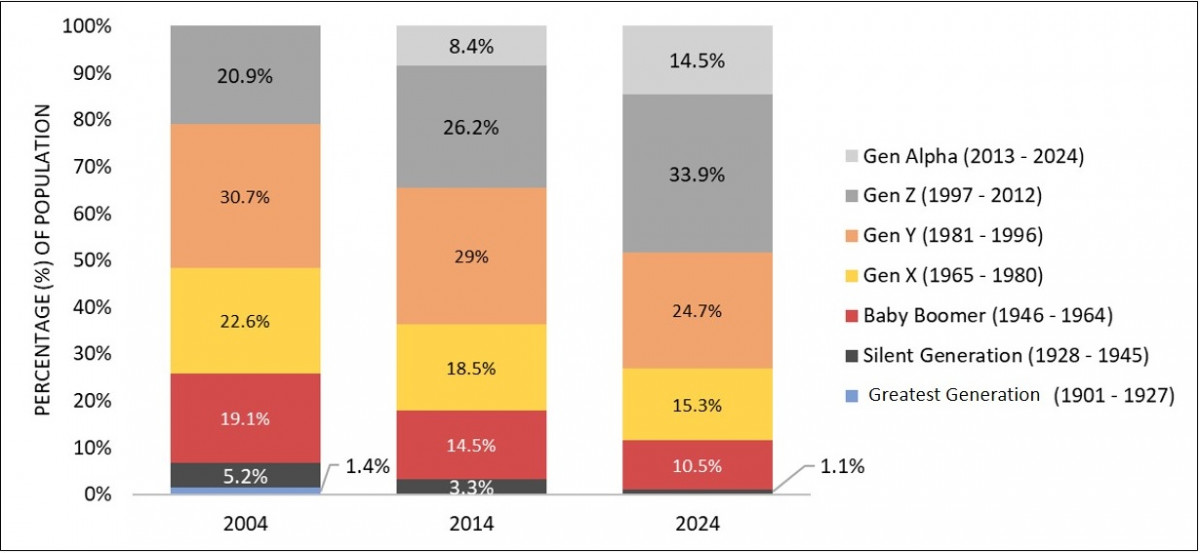

By 2024, Gen Z (33.9%) surpasses Gen Y (24.7%) to become the largest generation cohort in Malaysia (Figure 6). This is in stark contrast with a decade (2014) or two decades (2004) ago, when Gen Y (born 1981–1996) was considered the mainstay of the country’s housing market. Down the line, their unique perspectives and engagements are definitely shaping the future of real estate.

Furthermore, as technological advances and digitisation broaden access to information, consumers are no longer passive recipients of marketing messages. They are now able to thoroughly research different properties, compare prices, and critically evaluate various options, gaining a deeper understanding of market dynamics than ever before. These factors are conspiring to make consumers more cautious, value-conscious, and prudent before purchasing a home. Combined with economic uncertainty and a reluctance to make long-term financial commitments among younger generations, this growing hesitancy among consumers suggests a different outlook for housing demand from before.

Conclusion

The Malaysian property market continues to evolve under the pressure of a volatile macroeconomic environment and ever-changing microeconomic conditions. Yet, the industry is far from stagnant. Developers have demonstrated remarkable agility in adapting to demographic shifts, experimenting with new product formats, rethinking content strategies, and leveraging digital tools to stay competitive. They are increasingly aware that informed decision-making requires a combination of national and individual-level data; and understanding the strengths and limitations of each will enable more robust analysis, as well as ensuring more agile, buyer-centric, and insight-led strategies.

Given that the existing property data and information sources they rely on do not accurately reflect current market status, more nuanced metrics and market intelligence are critical to bridge the gap between optimistic public narratives and the practical realities developers face daily. Moving forward, the industry needs a more responsive “data ecosystem” to be in place, which not only can track buyers’ interest and product preferences on a real-time basis, but is also integrated with people’s purchasing power and loan application status, down to the level of locality; so that industry players can better interpret and tackle the multi-faceted views of market demand, buyer confidence, and prevailing conditions, allowing them to make informed decisions.

More importantly, this interconnected system will break down data silos, enabling organisations to gain deeper insights, make informed decisions, and create value from vast amounts of information by promoting data accessibility, quality, and security across industries; thereby enabling data transparency, smarter governance formation, and collaborative leadership.

As Penang girds itself towards the last lap of its Penang2030 vision, check out how the residential segment is keeping pace in EdgeProp’s special report: PENANG Investing Towards 2030.