- Unlike the conventional cross-subsidy model to provide affordable housing, where private developers and free-market house buyers are always on the “losing side”, a fairer resource allocation can be achieved through the “Madani Credits” system.

In many countries, the government plays a leading role in providing affordable housing, either directly through the construction and management of public or social housing or indirectly through subsidising the private sector to build affordable housing. In Malaysia, for decades, private developers have assumed a bigger role in providing affordable housing, with the government implementing affordable housing quotas — requiring a certain percentage of private houses to be capped at a ceiling price (ranging from RM42,000 to RM300,000) that is deemed affordable to the public.

The imposed obligation to the private sector may have helped to ease the burden of the government in providing affordable housing, but the main concern is that private developers face fundamental problems in building such price-controlled affordable housing, given that the development cost of affordable housing, especially in urban areas, often exceed the selling price set by the regulator, thus making the projects financially unviable.

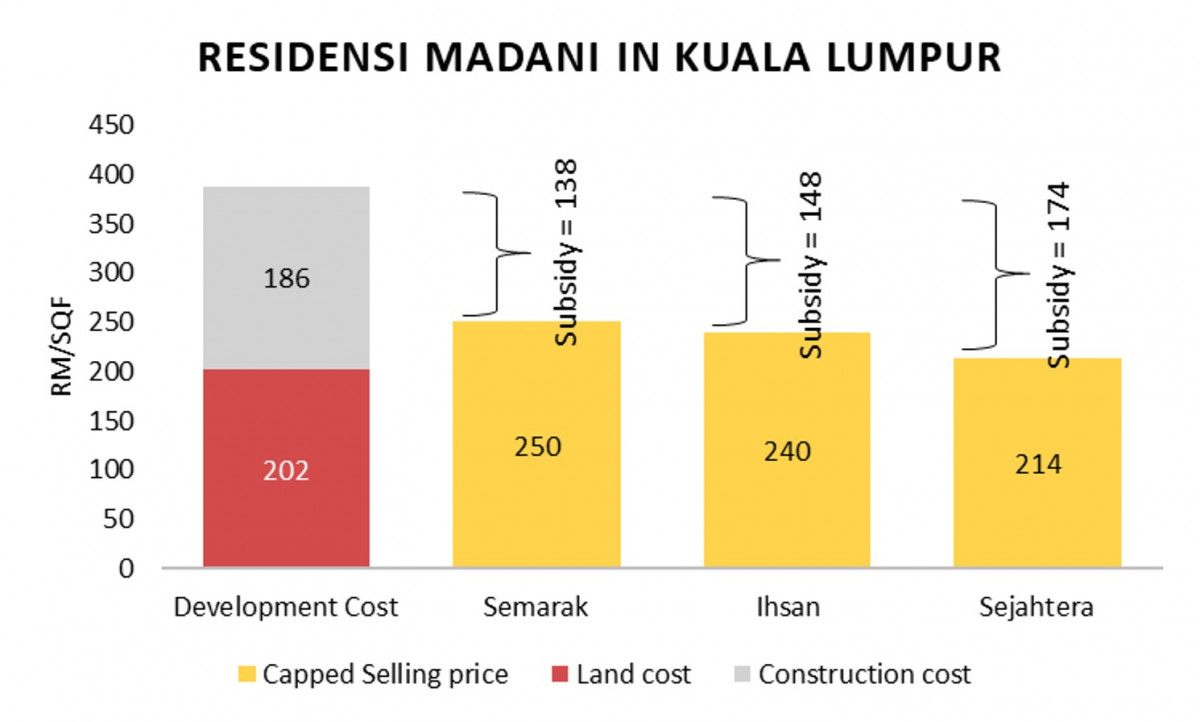

As shown in Figure 1, both the average construction cost (building + services) of an average standard apartment and median land price in Kuala Lumpur are RM186 psf and RM202 psf respectively. This results in Residensi Madani’s development cost of RM388 psf being higher than the selling price of Residensi Semarak (RM250 psf), Residensi Ihsan (RM240 psf), and Residensi Sejahtera (RM214 psf); even before including other costs like compliance cost, professional fees, financial charges, etc. The development of Residensi Madani is, thus, unsustainable to the entire housing market, as it requires substantial subsidies: RM510 psf for Residensi Semarak, RM520 psf for Residensi Ihsan, and RM546 psf for Residensi Sejahtera; which are passed on to the free-market house buyers.

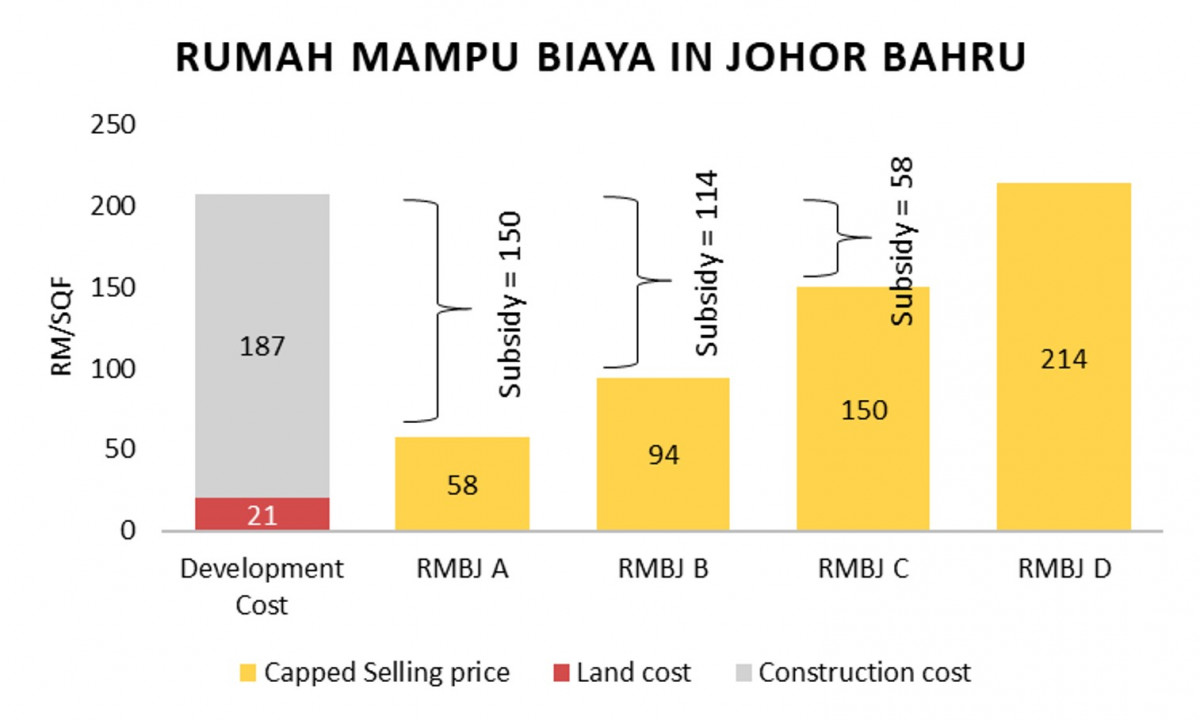

Likewise, the building of Rumah Mampu Biaya in Johor (RMBJ), especially in Johor Bahru, requires a subsidy of RM150 psf, RM114 psf, and RM58 psf for the respective RMBJ Type A, Type B, and Type C, to offset the high development cost of RM208 psf (Figure 2). This inevitably causes a deficit to be borne by the private sector that can only be “written off” through cross-subsidy from the free market housing.

The impact of cross-subsidisation on the overall housing industry is far-reaching, as it is not a sustainable practice that can encourage the property market to keep growing. More importantly, this cross-subsidy model is only suitable for large projects with economies of scale and during good market conditions. During downturns, where demand is very sensitive to price changes, this cross-subsidy model becomes unviable as the market cannot absorb higher priced free-market units that are factored into the cost of the subsidised units, not to mention that rising cost of doing business has further “squeezed” profit margins for free-market housing units.

Penang and Selangor’s affordable housing models more viable now

That being said, not all affordable housing schemes are alike. In some states, improvements have been made to ensure price-controlled affordable housing projects can be undertaken independently, with financially viable means, and more importantly, free from cross-subsidies.

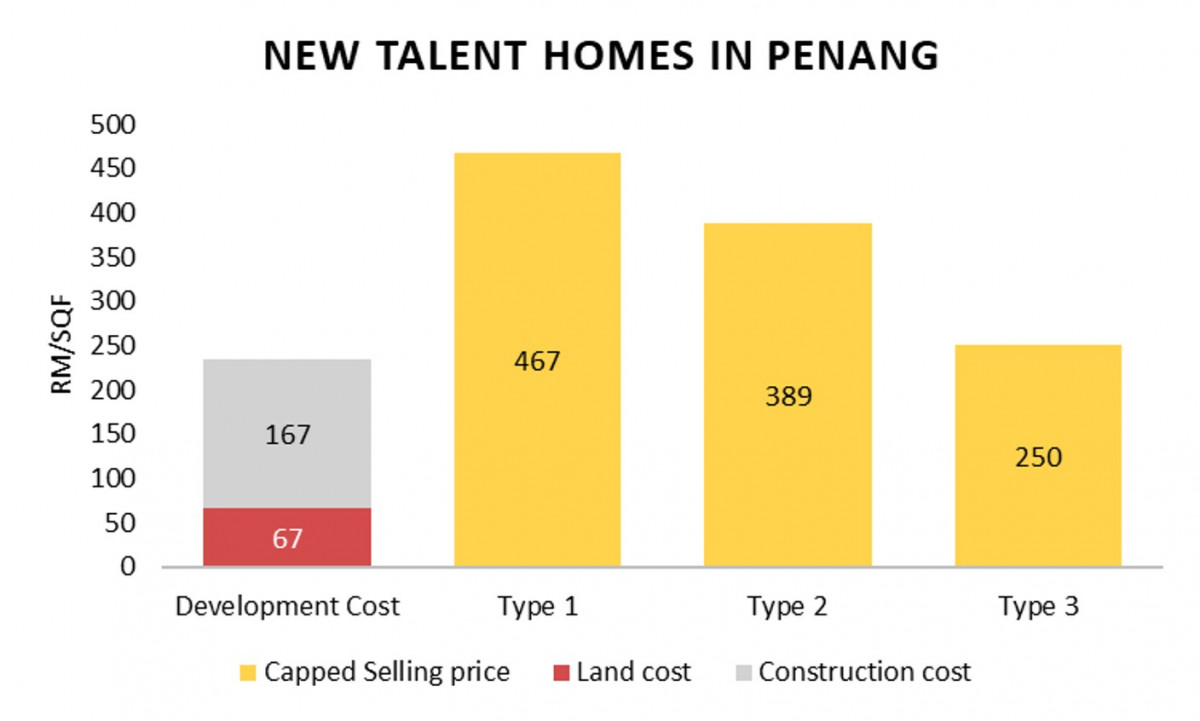

For example, Penang’s newly launched affordable housing model, the New Talent Homes, under the joint development between SkyWorld Development Bhd and Penang Development Corporation, has made price-controlled affordable housing development financially viable, by revising the capped selling price of affordable housing to a level above the development cost of RM234 psf (Figure 3).

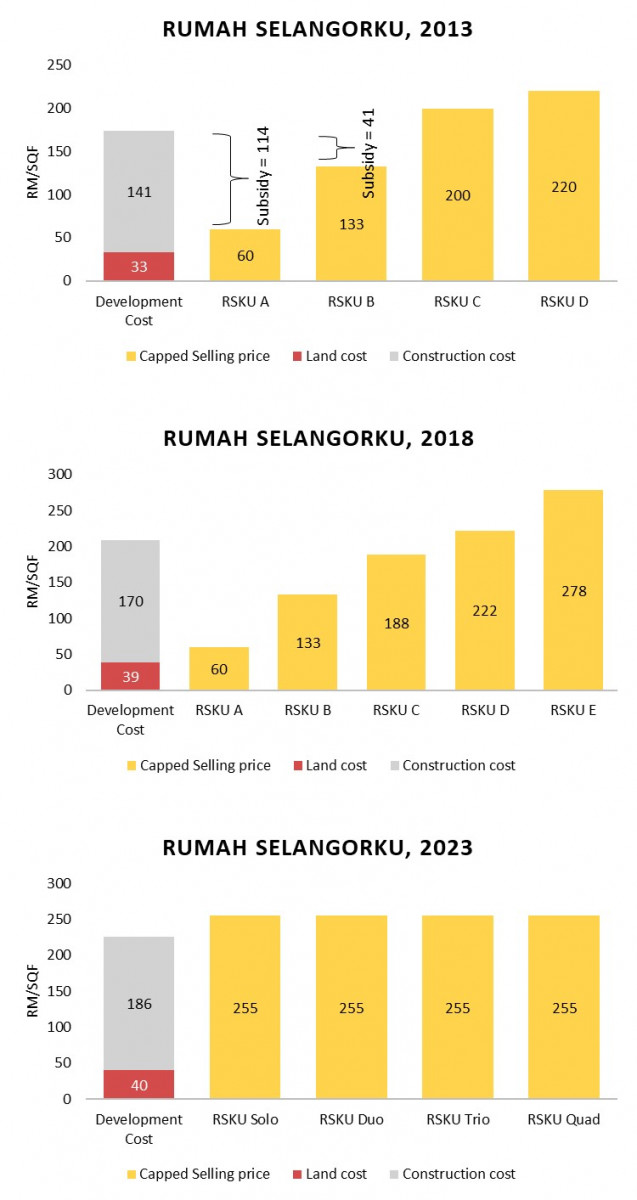

Similarly, the Selangor’s standards and specifications for building price-controlled affordable housing have been evolving over the years (2013–2023). Under the latest Dasar Perumahan Mampu Milik Selangor 2023 or better known as Rumah Selangorku 3.0, affordable houses that require substantial subsidies like RSKU Type A and Type B have been removed, while the selling prices for all types of affordable houses have been adjusted to a standard pricing of RM255 psf, which is higher than the development cost of RM226 psf (Figure 4).

Large-scale centralised development cheaper to build, easier to manage

Being a newly introduced affordable housing scheme that aims to help low-income citizens to own comfortable and quality homes in KL, the ceiling price of Residensi Madani should be adjusted to a reasonable level in line with the development cost in KL, so that no additional financial and operational burdens should be imposed on the private sector. More importantly, in the upcoming revision of the Garis Panduan Residensi Madani KL, the ceiling price of price-controlled affordable housing should keep pace with the rising development cost to ensure the long-run viability of the projects.

To uphold the development principles of providing a balanced and liveable ecosystem for the low-income groups in areas where land is scarce and is often costly; the government should consider a centralised development of Residensi Madani in one location, instead of imposing affordable housing quotas on each individual development site. This is because a large-scale centralised affordable housing development not only helps to lower down the unit construction cost, owing to its higher development density; but is also much easier to be planned and managed for both its social amenities and transportation networks.

This is in stark contrast to most current Residensi Madani projects, which are fragmented because only a small number of homes can be built on a small plot of land, and are often segregated from other free-market houses for the ease of management and fairness to homebuyers, as sale prices, maintenance fees and access to amenities vary. This not only creates undue financial hardship on private developers, but also free-market house buyers, as subsidies to small-scale price-controlled affordable housing projects are always higher, and will eventually be passed on to free-market house buyers.

To facilitate the construction of large-scale centralised Residensi Madani developments, joint developments of Residensi Madani units in multiple projects located in different parliamentary areas in KL should be allowed. Developers who wish to be exempted from building Residensi Madani on their project sites will fund and build such centralised large-scale Residensi Madani units on a cost-sharing basis, just like the collaboration of multiple private developers in undertaking the Integrated Water Supply Scheme (IWSS).

Affordable housing can be viewed as carbon-offset project

The government can even further think outside the box to establish a carbon credit-offset market as a potential source of funding for “green” affordable housing projects. Carbon-offsetting involves compensating for greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions by investing in projects that reduce, avoid, or remove emissions elsewhere. Building affordable housing can be viewed as a carbon-offset project if it incorporates sustainable practices, such as using green building materials, implementing energy-efficient designs, and reducing the carbon footprint of construction and operation.

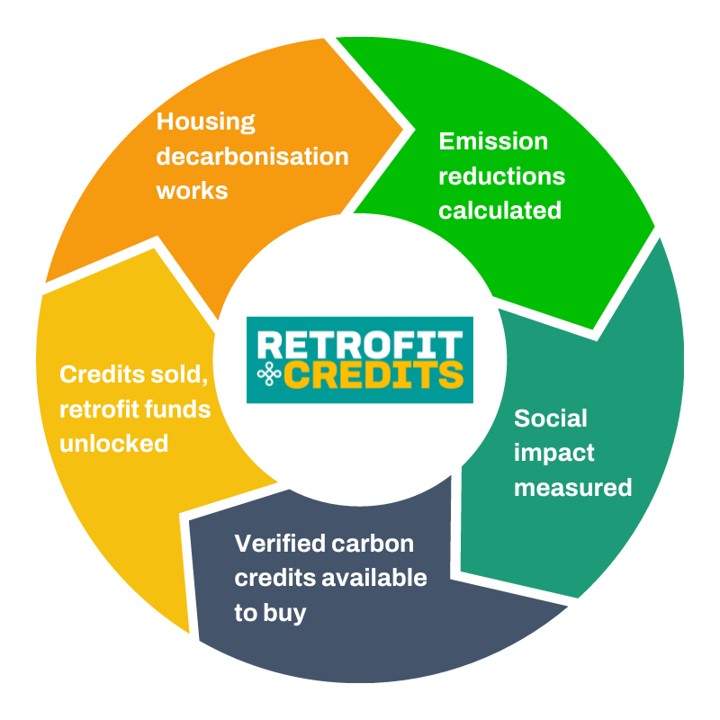

In fact, some organisations are exploring and implementing such strategies, by channeling offsetting efforts to fund locally-focused projects, such as retrofitting and renovating existing assets to maximise energy efficiency, reducing consumption, removing fossil-fuel connections, and advancing carbon removal technologies. A typical example of this is the Retrofit Credits, developed by the Head of Retrofit Credits (HACT) in partnership with PNZ Carbon, which is an innovative carbon credits scheme designed to finance and accelerate the decarbonisation of social housing in the UK.

This initiative is unique because it not only focuses on reducing carbon emissions but also integrates social value into its framework, ensuring that the benefits of retrofitting homes extend beyond environmental impact to improve residents’ lives. The scheme works by verifying the emission reductions achieved through retrofitting projects in social housing and translating these reductions into carbon credits. These credits are then sold to investors and organisations aiming to offset their carbon footprints, with the revenue reinvested into further retrofit projects. This creates a cycle of continuous improvement, where social housing providers can access new funding streams to enhance the energy efficiency of their properties (Figure 5).

Unlike traditional carbon credits, which focus solely on GHGs emission reductions, one of the most standout features of this Retrofit Credits is its commitment to social value, by taking into account the positive impact on residents, such as improved health, comfort, and reduced fuel poverty. This dual focus makes it a pioneering approach, combining environmental and social outcomes in a way that is not seen in other carbon-credit schemes. The initiative has seen previous success by garnering interest from a variety of buyers, including major organisations like The Economist Group and Unity Trust Bank. The scheme remains in a growth phase, looking to deliver more impact by partnering with more social landlords and the private sector.

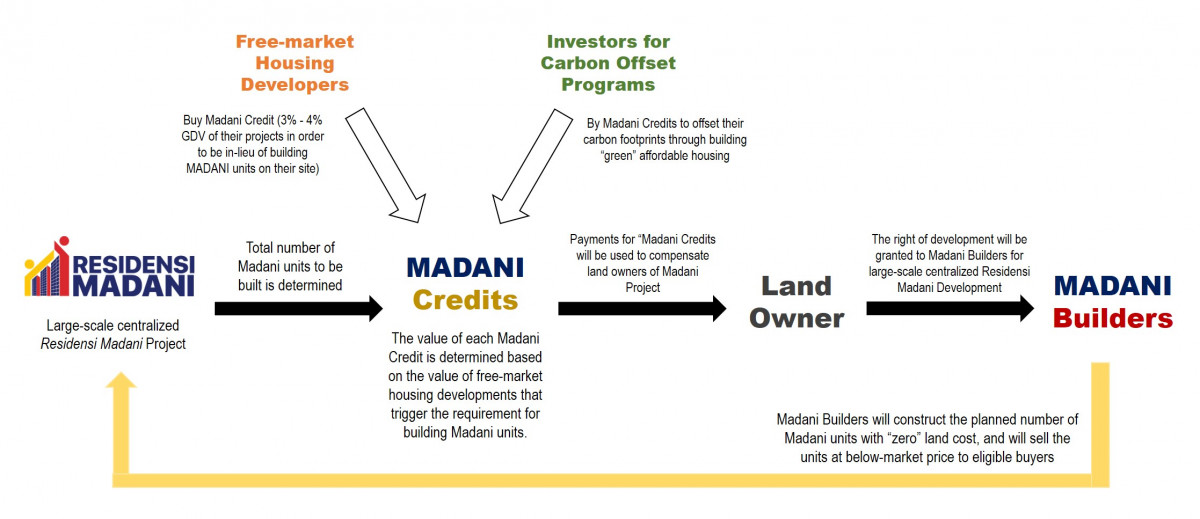

Perhaps, a market-based solution resembling the Retrofit Credits could be established to improve the feasibility of building Residensi Madani in KL without causing any financial hardship to private developers and free-market house buyers. The government can launch the “Madani Credits,” in which the value of each “credit” will be determined based on the number of price-controlled units to be built on the land plots allocated for the development of centralised Residensi Madani projects, and the value of free-market housing developments that trigger the requirement for building Residensi Madani units.

Developers who wish to be exempted from building Residensi Madani on their project sites can buy “Madani Credits” which cost, let’s say, 3% to 4% of the gross development value of their free-market housing projects. These developers will be free from providing Madani units on their project sites, thus allowing them to unlock the true value of their land and contribute to free-market housing products that meet local needs. It is important to note that the value of “Madani Credits” should not be set too high, because a higher value will serve as an indirect cost to be passed on to the free-market house buyers, which is another form of cross-subsidisation.

Land owners can adequately recover compensation from ‘Madani credits’

The payment for “Madani Credits” contributed by these developers will be used to compensate land owners whose lands are to be used for the large-scale centralised Residensi Madani developments. Depending on the land size and the number of Residensi Madani units to be built on the lands, compensation to the land owners will be different.

Given that there are many active new launches with high selling prices for free-market properties in KL (the Edge Prop new-launch report shows there are 187 projects with a total 134,448 units between 2025 and 2028 in KL), the combined contributions from all these developers would be more than enough to ensure land owners get their compensation duly according to market value.

Besides, these “Madani Credits” can also function as Carbon Credits which can draw investments from other organisations aiming to offset their carbon footprints through building “green” affordable housing. This additional source of funds can be channelled into the development of Madani units by incorporating sustainable practices throughout the building process and operation, from material selection to energy efficiency. More importantly, this is not a “one-off” funding as it can resemble the function of Retrofit Credits to unlock additional funding into housing retrofit by verifying the emission reductions and social value of retrofit projects.

Price-controlled Residensi Madani units that are affordable to low-income groups will be built and sold by the “Madani builders,” which are normally contractors-turn-developers that specialise on the construction of mass volume affordable housing. Since the land cost is zero (as the land owner is compensated by the “Madani Credits”) and the number of Madani units to be built is large; “Madani builders” will enjoy lower development costs that can guarantee the projects’ feasibility. Besides, the below-market selling price of RM200,000 per Madani unit should be fully sold easily.

The proposed “Madani Credits” system (Figure 6) not only offers a breakthrough for building price-controlled affordable housing on high-cost lands, but also ensures a “tripartite win-win situation” among free-market housing developers, land owners, and “Madani builders. Unlike the conventional cross-subsidy model where private developers and free-market house buyers are always on the “losing side,” a fairer resource allocation can be achieved through the “Madani Credits” system. Free-market housing developers will no longer be burdened with the sole responsibility of providing economically unviable price-controlled housing. By relieving them from the mandatory affordable housing quotas, they will be better positioned to supply high-quality free-market housing in line with current market demand.

Likewise, the “Madani builders” will become more specialised and focused on affordable housing development to meet the needs of the low-income group, while the land owners will be treated more fairly since the true value of their lands is no longer restricted. Eventually, a more committed, sustainable, and transparent fund allocation for affordable housing development in the long-run is formulated that helps the country to achieve its goals of economic growth, social stability, and improved quality of life for its citizens.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is the principal researcher from MKH Bhd. The views expressed are the writer’s and do not necessarily reflect EdgeProp’s.

Want to have a more personalised and easier house hunting experience? Get the EdgeProp Malaysia App now.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Pavilion Damansara Heights

Damansara Heights, Kuala Lumpur

Pavilion Damansara Heights

Damansara Heights, Kuala Lumpur

Austin Residence @Taman Mount Austin

Johor Bahru, Johor

Bandar Baru Sungai Buloh

Sungai Buloh, Selangor