Abu Kassim had been staying at a condominium for 12 years, diligently paying his dues.

Unfortunately, the housing developer suddenly wound up. At that material time, all the strata titles had been issued by the Land Office and were in the possession of the then defunct developer.

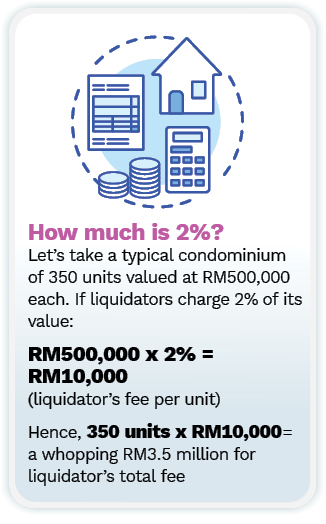

As per normal regulations, a liquidator was appointed to take custody of the development. As part of his duty in performing the functions of a developer, the liquidator was to arrange for the owners’ collections of their strata titles. To the latter’s consternation though, the liquidator arbitrarily imposed charges of 2% of the original purchase price or the sale price in a sub-sale, whichever was higher.

Abu Kassim was shocked by the double jeopardy especially when he had paid the entire purchase price to his developer. He couldn’t afford to pay the liquidator’s demanded “fees” on top of the requisite stamp duties.

He was left in a dilemma as the liquidator imposed a deadline to collect the titles, failing which the latter threatened to auction the unclaimed units.

The above scenario happens quite often in situations involving defunct property developers. These complaints are not something new to the Malaysian Department of Insolvency (MDI) and National Housing Department under the auspice of the Housing and Local Government Ministry.

Delivering a project on time and in a satisfactory manner is the primary duty of a developer. In addition, the developer must also procure the issuance of individual titles and subsequently assist in transferring the titles to the purchasers.

However, things get complicated when a developer is compulsorily wound up pursuant to a court order (mostly due to inability to pay debts) before individual titles have been issued and transferred to the rightful purchasers.

In the absence of an individual title and as a matter of procedure, a purchaser will have to obtain written confirmation from the developer before the property can be assigned to another owner.

The unhealthy practice of liquidators imposing exorbitant administrative fees up to 2% or 3% of the purchase price (or in some cases, current market value of the properties) for executing the transfer of individual titles to purchasers has now become a norm.

The fee is purportedly used to cover the liquidator’s costs in retrieving the related documents which have been purportedly destroyed or misplaced by the developer and verifying the same with the purchase proofs provided by purchasers. Consequently, a straightforward perfection of transfer becomes a costly affair.

Unilateral impositions of such fees by liquidators are devoid of any legal basis. Furthermore, the sum imposed is ridiculously high and is far more than enough to cover reasonable administrative costs involved.

This casts doubt on the motive of collecting such fees and raises the question of whether the liquidators are unjustly enriching themselves at the expense of bona fide purchasers who are already in precarious positions without their individual titles.

Read also

Victims of runaway developers face double woes from exploitative liquidators

Liquidators merely ‘bare trustees’

It is an established principle of law that upon full payments by purchasers, a developer becomes a “bare trustee” of the property. In other words, once a developer has received the full purchaser price for a property, the developer is no longer the real owner of the property. The developer is merely holding the same property in trust for the benefit of the purchaser. The developer, as a bare trustee, has no beneficial interest in the property. It follows that a developer cannot deal with or treat the property as belonging to itself.

Once a liquidator is appointed, he steps into the developer’s shoes. It follows that the liquidator assumes the same role as a bare trustee and is not entitled to any other benefits more than the developer.

Similarly, a liquidator is not authorised to deal with the property other than to transfer the property to the rightful purchasers. Pending transfer of titles to purchasers, the liquidator is acting as an “interim caretaker” to the sold property. As a bare trustee, the liquidator is not allowed to profit himself using the trust property.

A breach against housing legislation

One of the amendments to the Housing Development (Control & Licensing) Act, 1966 (Act 118) (HDA), which took effect on June 1, 2015, namely Section 3 of the interpretation, extends the definition of “housing developer” to include “a person or body appointed by a court of competent jurisdiction to be the provisional liquidator or liquidator for the housing developer”.

The amendment to include a liquidator as a “housing developer” was intended to fill the void when a developer is wound up before completion of its duties and contractual obligations under Act 118. Its duties include to complete construction of the buildings or facilities, deliver vacant possession and apply for individual or strata titles, thus not leaving the purchasers in a lurch.

As a result of said amendment, a liquidator will be subjected to the duties and responsibilities imposed by HDA and may be liable for breach of duties of a “de facto” housing developer.

In theory, a liquidator should not be allowed to charge or impose any additional administrative fees when carrying out his duties since he is assuming the affairs and responsibility of the defunct developer contracted in the sale and purchase agreement (SPA).

Section 22D(3) of the HDA provides inter-alia:

A housing developer (in this case, liquidator) shall keep and maintain an up-to-date, proper and accurate register of all purchasers of the housing accommodation until separate or strata titles for all the housing accommodation in the housing development have been issued by the appropriate authority and registered in the names of all the purchasers of the housing accommodation in that housing development.

With a proper record of purchasers, liquidators will hardly face any difficulty in issuing written confirmations when requested to do so. It is for this reason the HDA provides that a developer is only allowed to collect a fee not exceeding RM50 for issuing a written confirmation. (Refer Section 22D(4).)

The SPAs adopting the statutory format set out in the Housing Development Regulations 1989 have been consistently regarded by the courts of law as having the effect of statutory provisions. The agreement provides that it is the developer’s duty to execute the transfer documents upon issuance of individual titles in favour of purchasers.

By collecting administrative fees above and beyond the cap set out in the HDA, the liquidators are effectively seeking a “fee” to perform something which they are required under the law to perform anyway.

Why should property buyers be held to ransom?

Liquidators are appointed by the court to manage the affairs of wound-up companies as far as is necessary to realise the company’s assets and pay up creditors. As such, they are considered as performing their duties on behalf of the court and are viewed as “officers of the court”.

In addition, as a bare trustee, a liquidator is expected to diligently carry out the duty to verify the purchaser’s record whenever required to do so and should not be allowed to gain profit other than those expressly allowed by the court when discharging the duty imposed upon him as an officer of the court.

While liquidators should rightfully be reasonably remunerated for carrying out their duties, their gains are supposed to be from the sale and realising of the defunct company’s assets, including from the unsold stocks in the housing projects. If there is no money to make from this process, then the liquidators have the right to decline the appointments in the first place.

They should not attempt to impose extra “top-ups” on already burdened victims of an abandoned housing project. Their remuneration must be in accord with the Companies Act 2016.

If at all the liquidators are allowed to collect administrative fees, the fee should be kept at a reasonable level for the purpose of covering the liquidators’ expenses in retrieving and verifying the purchase records of housing projects. Any attempts to seek additional profit beyond what is statutorily allowed should be stopped. Liquidators must not be allowed to hold the purchasers to ransom.

After all, individual and strata titles are not assets per se; they are purchasers’ ownership papers.

This article is jointly written by Datuk Chang Kim Loong, the Hon Sec-general of the National House Buyers Association (HBA), and HBA volunteer lawyer Koh Kean Kang, Esq.

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.hba.org.my

Tel: +6012 334 5676

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my E-weekly on July 9, 2021. You can access back issues here.

Get the latest news @ www.EdgeProp.my

Subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest stories and updates

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Sendayan Tech Valley Industrial Park

Siliau, Negeri Sembilan

Senada Residences @ KLGCC

Mont Kiara, Kuala Lumpur

Setia Marina 2, Setia Eco Glades

Cyberjaya, Selangor

Summerglades, Perdana Lakeview West

Cyberjaya, Selangor

Isle of Kamares, Setia Eco Glades

Cyberjaya, Selangor