Property Chat: Assessing the health of the Malaysian housing industry

The Buffett indicator – defined as “the total market capitalization of stocks divided by the total value of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP)” – has been widely used for gauging the broad stock market valuation in a country. The indicator is similar to the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of a particular stock, where it gives investors a sense of potential future yield over the long-run. Hence, while Buffett indicator is not a timing tool, it does provide an insight on where the market is currently at, thereby contributing towards risk reward assessment in portfolio management.

Likewise, in assessing the valuation of a country’s housing market, the ratio between the total real estate value over the country’s GDP, coupled with other fundamental indicators such as price-to-income ratio, price-to-rent ratio, the number of existing stock-to-household ratio etc., will give a guesstimate on the health of the housing market in the country. A high Buffett indicator compares to its historical average does not indicate the real estate sector is in a bubble; but it does show a high-risk low-return proposition for real estate market in long-term due to the high market valuation. A cross-country comparison on the real estate ratio in GDP multiple can even provide an overview on how the role of real estate across the world is changing, as well as indicating if the real estate price growth in a country has exceeded the international level of economic development.

Globally, real estate is the most important asset class, along with other assets like commodities, equities, and bonds. More importantly, it accounts for a significant proportion of personal and household wealth in developed economies. Despite a high degree of uncertainty around the path to economic recovery from Covid-19, the real estate value reached US$326.5 trillion (RM1.379 quadrillion) in 2020, which is 4.0 times the world’s GDP at the time; as compared to the value of US$280.6 trillion in 2018 and US$217 trillion in 2015, which were 3.5 times and 2.7 times the world’s GDP at the time, respectively. However, as the ratio climbs, the return for real estate investment per unit of risk continue to decline.

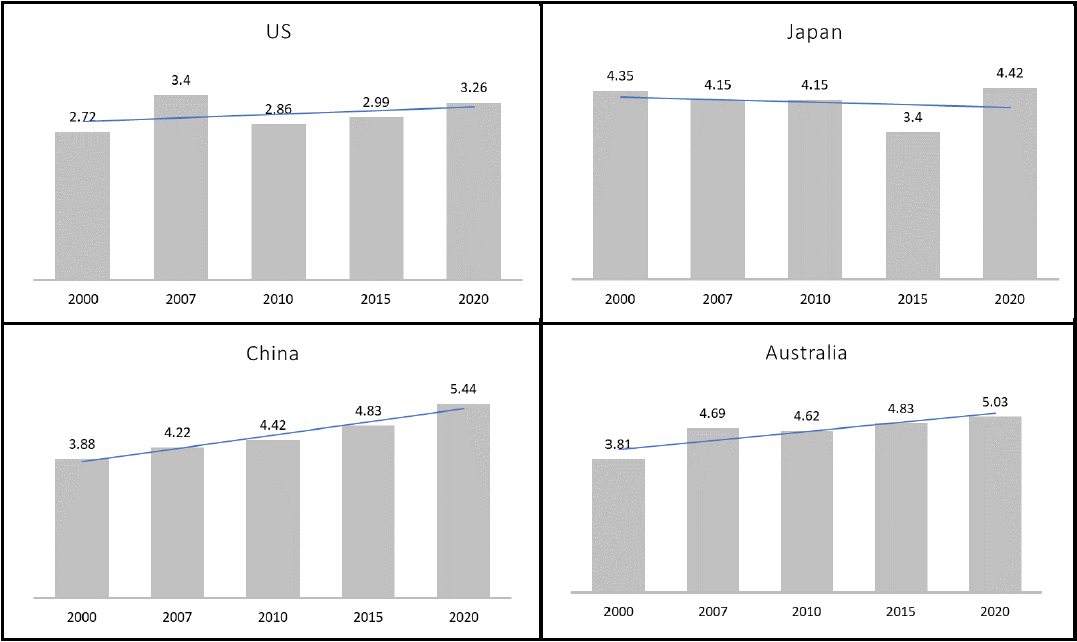

By studying the dynamic of the ratio from some of the top-10 most valuable real estate markets in the world – China, US, Japan, Australia – one can find that the real estate ratio in GDP multiple for the United States climbed from 2.72 in 2000 to 3.4 in 2007 (Figure 1). After the economic collapse due to the Subprime Mortgage Crisis in 2008, the ratio went down to its pre-crisis level, and recovered slowly despite massive quantitative easing and low interest rate policy by the US Federal Reserve for 13 years. In 2020, the ratio still stands at 3.26, well below the height reached in 2007. This is not the first time that the ratio went down and flat for years after the real estate market went bust. In Japan, a similar trend is observed after the 1990 Asset Price Bubble burst, where the ratio has been shrinking from as high as 3.91 in 1990, in conjunction with the period of economic stagnation and price deflation known as “Japan’s Lost Decade”. Though the ratio reached 4.42 in 2020, a general declining trend is still prevalent throughout 2000 – 2020, signifying the country is still undergoing consolidation for its real estate market.

The example of dwindling returns versus heightened risk with a rapidly rising Buffett Indicator can be seen in the Chinese real estate market when the country’s second largest real estate developer – Evergrande – defaulted on its bond in late September 2021. The liquidity crisis faced by the ‘Fortune Global 500’ company highlighted the fragility of the real estate market associated with high Buffett Indicator of the country, as the real estate ratio in GDP multiples has been rising steadily from 3.88 in 2000 to 5.44 in 2020.

Whether this ratio will be trending downwards (like Japan) or sideways (like the US) for the next decade still remains unknown. But by benchmarking it against other countries’ real estate market size – where the China’s real estate market value in 2018 is US$47 trillion, surpassing the one for the United States (US$26 trillion) and Japan (US$10 trillion) – global real estate investors would certainly have better return investing in other countries with a rather moderate historical ratio over GDP. This is because – throughout the development of the Buffett indicator – the ratio for major countries will first reach its periodical peak before the financial crisis or the burst of the real estate bubble, followed by a downward trend in years, and only to return gradually to its pre-crisis level after hitting its bottom level.

Like China, the Australian real estate market has been experiencing a drastic expansion over the past two decades, seeing the ratio increases from 3.81 in 2000 to 5.03 in 2020. Lately in October 2021, it is announced that the market size has surpassed a new record of A$9.3 trillion (RM28.02 trillion), in which the dwelling values are 21.6% higher over the past 12 months, and even being the highest annual appreciation since June 1989. While such market size is considered relatively smaller than the one held in China, US, and Japan; a high ratio of Buffett indicator is certainly signifying a high-risk low-return proposition for the Australian real estate market due to overpricing or overheating.

Back to Malaysia, the housing market has been languishing after experiencing a double-digit house price growth (CAGR of 11.4%) in 2007 – 2014. With the economic slowdown and the implementation of a series of speculation-curbing measures since 2014, the Malaysian housing market enters into the period of adjustment. The sign of financial distress in the country becomes even more significant as the lingering impact of the pandemic bites deeper into the country’s economy in 2020 and 2021. Given the falling rental yields and the low house price growth for the past few years, especially during the outbreak of the pandemic, the country’s housing market is said to be undergoing the transition from a favorable environment for buying a house towards a situation which is less attractive for property investment.

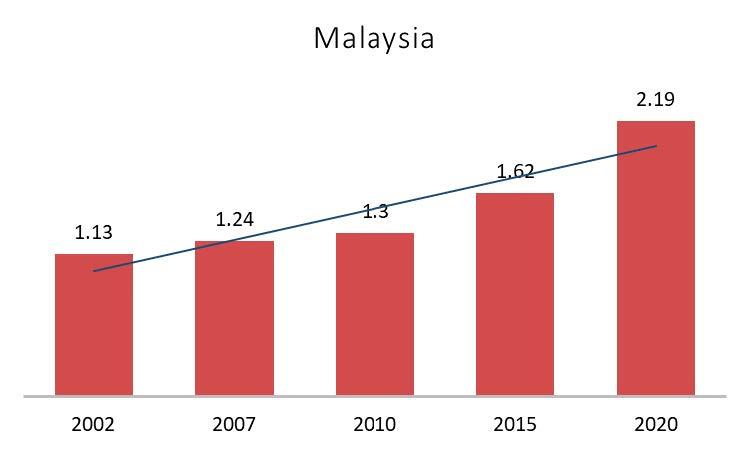

Having said that, the Malaysian housing market is not yet at the high-risk low-return proposition as experienced by the above-mentioned countries, not even at the risk of bubble as claimed by some scholars. This is because, when judging from the perspective of the real estate ratio in GDP multiple, though it is increasing from 1.13 times in 2002 to 2.19 times in 2020, such a moderate market size is rather rational and manageable, signifying a positive growth condition for its housing market (Figure 2).

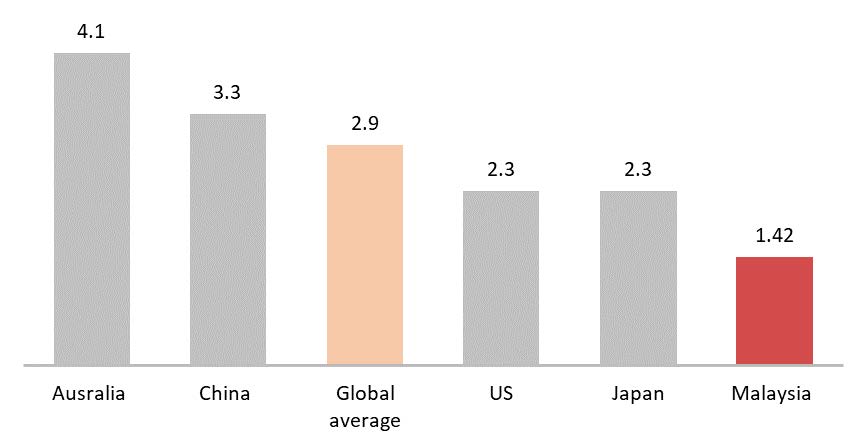

In terms of household exposure to real estate, despite having high household debt, Malaysian household only have minimal exposure to its real estate sector. Its Buffett Indicator is at 1.42 compared to the global average of 2.9 (Figure 3). This could be due to the stagnant or marginal growth of household income that leaves families with limited discretionary cash to participate in the real estate market. Meanwhile, the country is still in the process of shifting to a high-value economy in order to boost household income.

This is in contrary to country like Australia, having high household exposure to real estate market as indicated by the Buffett indicator at 4.5, which is the highest even compared to Japan and US. This could be due to the fact that Australian households have never experience a recession for almost 30 years; while the confidence of households in Japan and US has been deeply scarred and require longer consolidation time to heal after the crisis in 1990 and 2008.

In this regard, the Malaysian housing market size multiples still have room to expand. Though developers may find it difficult to sustain consistent growth due to current challenges in both the local and global economies, the fundamentals of the housing market still remain intact in the long term as the Malaysian economy continues to grow, coupled with the rising population, increasing demand for better quality of living, improvements in infrastructure etc. As shown by the Buffett indicator, rationally, the downsides are limited and the current valuation of the Malaysian real estate market is favourable for long-term investment.

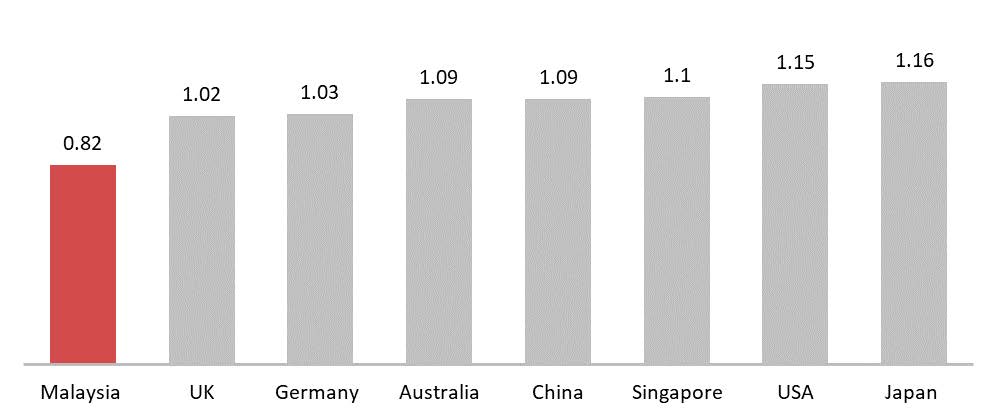

When it is assessed from the perspective of the number of existing stock-to-household ratio – which is mainly used to examine if there is an imbalance between the supply and demand of housing in a country – one can find that the ratio for Malaysia is 0.82, which is less than 1, indicating the country’s housing supply is generally insufficient. This is in contrast to the rest of the countries, having a ratio of more than 1 that indicates the abundance in supply (Figure 4).

By taking into account the vacancy and occupancy rates, demand for leisure and vacation, as well as the separation of residences due to population mobility etc., the number of existing stock-to-household ratio for a mature market should be around 1.1. In this sense, Singapore is in the stage of supply-demand balance; while US and Japan are in the stage of oversupply, with both the ratio of 1.15 and 1.16, respectively. In terms of Australia and China, both their ratios are 1.09, – which is close to 1.1 – indicating that there is basically no housing shortage in these countries but the housing market is rather moving towards a new cycle of high-quality development that emphasizes on improved quality and slower speed of production. From here, one can definitely have some ideas on how much room of growth for the Malaysian housing market in the next decade.

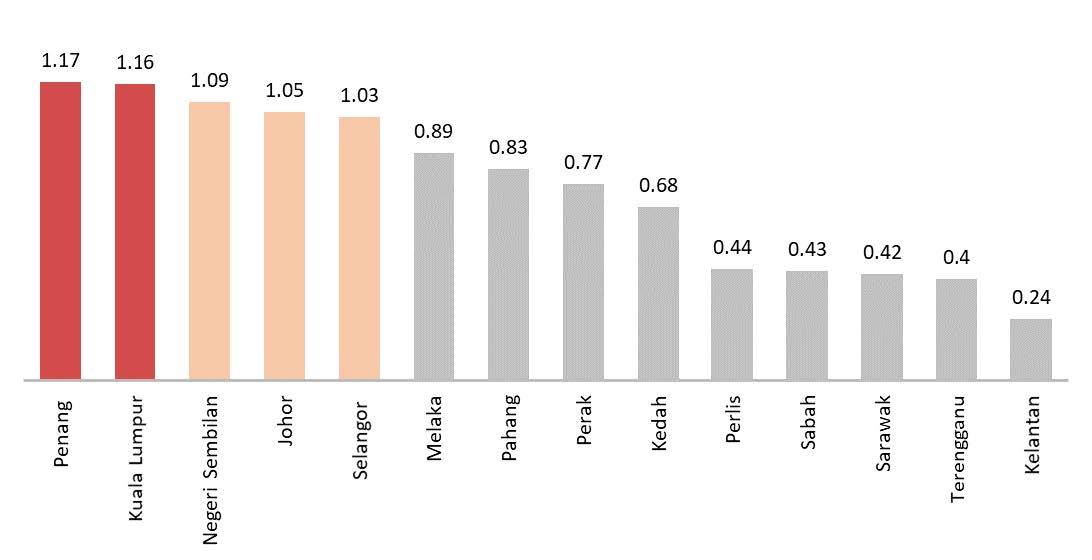

However, when it is assessed from the state or regional level, one can find that ratios for areas like Penang (1.17) and Kuala Lumpur (1.16) are higher than 1.1, far exceeding the national-average ratio (0.82) (Figure 5). Even other prime markets like Negeri Sembilan (1.09), Johor (1.05), and Selangor (1.03) are approaching the “near-to-saturation” status in terms of supply-demand, signifying that high-growth stage featured with the speculation herd instinct and rapid expansion in investment volume is becoming less and less prevalent in these markets. Rather, these markets will be led by those rational demands emphasizing on own-stay and self-occupied, lifestyle living and upgrading, as well as higher quality consumption. Thus, investors who are still interested with the Malaysian housing market should be sensitive to such a domain differentiation in each individual local market, in order to establish a productive long-term real estate investment strategy and management mechanism. As for the rest of the areas with a ratio of lower and 1, market expansion in volume will continue due to the intensifying urban agglomeration process, increase in household income, and the decrease in household size.

Overall, there is still room for improvement in the Malaysian housing market, as the country is capable to offer a relatively low-risk and moderate-return investment opportunity in the long run. However, caution should be taken as some regional/local markets have started to see an inflection point in their growth rate – the prime markets in particular – which is a sign of a mature market.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is the principal researcher of MKH Berhad and Wong Gee Way is a real estate analyst of Leverage Value Sdn Bhd

Follow Us

Follow our channels to receive property news updates 24/7 round the clock.

Telegram

Latest publications

Malaysia's Most

Loved Property App

The only property app you need. More than 200,000 sale/rent listings and daily property news.