When buying a new property, people often consider the price, the condition of the property, the views it offers and so on, but seldom do they ask whether the property is ‘green’ or even energy-efficient.

According to the Malaysia Institute of Architects or Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia’s (PAM) Green Building Index (GBI), green buildings are defined as those that focus on improving the efficiency of the use of resources such as energy, water and materials while reducing the impact on human health and the environment throughout its lifecycle.

PAM president Lillian Tay tells EdgeProp.my that one of the hurdles to the wider acceptance and adoption of green buildings is the lack of awareness, which is partly due to insufficient marketing by developers.

“For example, even when a building is certified green, we see the air-con is turned on when the developer is handing over units in the building to buyers. A better way is to keep the air-con off to show the buyers that the interior is cool due to the building’s green features,” she shares.

Many people also believe that green buildings are expensive and cut them off their list straightaway.

According to GBI’s published data, incremental construction cost of going green (inclusive of material cost and technology cost) ranges from 0.7% to 11%. There are also registration and renewal fees.

The government is giving tax deductions to GBI-certified buildings where building owners could enjoy income tax deductions equivalent to the additional capital expenditure needed to obtain the GBI certification.

“Although an increment in initial cost is required, GBI-certified buildings could yield at least 30% to 40% energy savings for its dwellers compared with the average baseline building. Higher energy savings could be achieved in buildings with higher levels of certification,” Tay says.

Cost-saving buildings

Since its inception in 2009, GBI has certified 500 projects in Malaysia, covering a total gross floor area of 22 million sq m as at June 2019.

With mindful design, daily power and water consumption could be reduced, hence lowering the respective expenses. This is made possible by the GBI requirements on aspects such as building design, building materials as well as the installation of energy- and resource-saving fittings.

For instance, the right passive design does not require much additional cost, but could reduce solar heat gain into the building.

Related strategies include optimising balance between solid walls and glass for sufficient natural light but not too much heat gain, choosing better building orientation, providing enough shading and leaving space for natural ventilation.

With less heat transmitted into the building, air conditioning and fan usage could be reduced. According to the Greening

Malaysia book published by PAM, GBI-certified buildings have an overall thermal transfer value (OTTV) of 42.3W/m2 on average, 15.6% lower than the minimum thermal performance specified by the Malaysian Standard: MS1525. OTTV is a measure of average heat transmitted into a building through the building envelope.

GBI-certified buildings in the country record a total electricity usage reduction of 776 million kWh per year — equivalent to the annual energy consumption of 195,390 households or 2.4% of total Malaysian households.

Total savings on energy cost reached RM388 million a year or an average energy cost saving of RM803,000 per year for a single building. “And the savings will repeat every year,” Tay adds.

Meanwhile, renewable energy generation by GBI-certified buildings reached 23.3 million kWh per year, equivalent to electricity used by 5,864 Malaysian households every year.

When it comes to building materials, high-performance glass can keep the heat out and at the same time allow light to come into buildings while a good-quality building envelope could reduce heat transmission from the sun.

Installing devices such as power-saving lights, high-efficient air-con system and water-saving toilet fittings could also help reduce energy and water usage. GBI-certified buildings saved a total of 19.4 billion litres of water per year — thanks to rainwater harvesting systems, water recycling and water efficient fittings.

‘Green’ is not only about saving energy after the building is completed but also involves the construction process.

Buildings that comply with GBI requirements have diverted 197,500 tonnes of construction waste from landfills to recycling centres. The Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) in November 2015 said it is estimated that construction and demolition works account for over 30% of total waste generated in Malaysia.

On the other hand, overall carbon dioxide reduction from GBI-certified buildings have reached 1.12 million tonnes per year.

More should be done

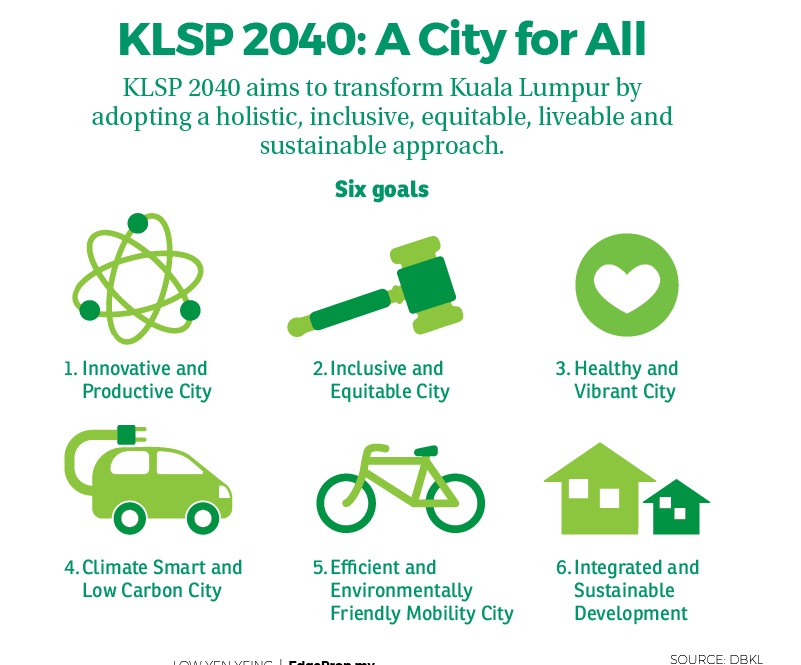

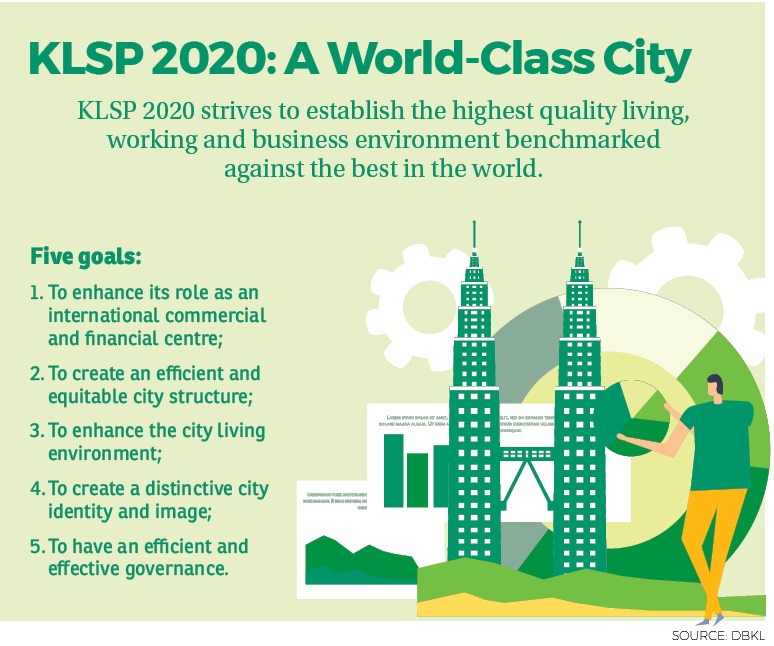

Meanwhile, the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2040 (KLSP 2040) has put more emphasis on sustainability compared with the old KLSP 2020 where the city will strive to become a low carbon and resource-efficient metropolis.

”For sustainable living, I believe we must now begin to promote better energy efficiency for buildings,” Tay stresses.

However, even with KL City Hall (DBKL) opting for a more sustainable future, the rest of Malaysia may not be heading the same way as there is no centralised body to look into the overall planning of the country’s development sustainability.

In Singapore for instance, its Housing & Development Board (HDB) regulates a large part of the country’s housing, hence the country has been able to maintain focus on sustainability in urban development. The island republic also needs to give priority to sustainable development due to scarcity of land and natural resources.

“In Malaysia, local authorities in the various states have different standards such as on planning and building approvals. The authorities should adopt the same sustainability principles in their planning criteria for new developments and buildings,” Tay opines.

“A slightly higher initial cost today could bring cost savings on energy for the long term. The effect is cumulative, on top of reduced environmental impact and carbon footprint,” she says.

“Apart from efforts by the government, every development, building owner and developer should do their bit, so that we could achieve the positive impact that we want,” she concludes.

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my pullout on March 20, 2020. You can access back issues here.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Damansara Heights (Bukit Damansara)

Damansara Heights, Kuala Lumpur

Medan Mega Melati M3 Residency

Setapak, Kuala Lumpur

Anggun Residences (Anggun JS 1)

KL City, Kuala Lumpur

Taman Sutera Lama

Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan

Seri Baiduri

Setia Alam/Alam Nusantara, Selangor