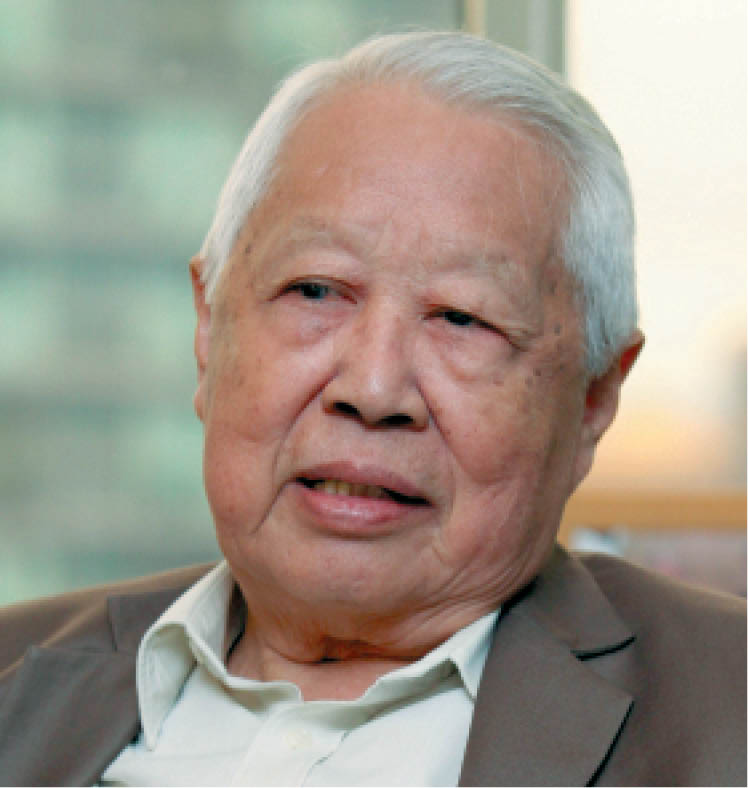

"WHAT I like the most about the job is designing. It is something you can dream about and you can put in your talent, aspirations for the future and what you would like to see in Malaysia. It allows you to create things that tell stories and inspire. Isn’t it important that you can inspire? How many people have the opportunity? It is more than just earning money,” renowned architect Hijjas Kasturi tells City & Country recently.

Born in Singapore in 1936, Hijjas received his secondary education at Raffles Institution, after which he became a draughtsman at the Singapore Housing Trust. The Australian government awarded him a Colombo Plan grant to study in Adelaide and then Melbourne, Australia, where he graduated in Architecture and Town Planning in 1965.

He returned to Singapore the following year and moved to Malaysia in 1967, where he founded the School of Art and Architecture at Mara Institute of Technology. He went into partnership in 1969, and set up his own practice — Hijjas Kasturi Associates — in 1977.

The Colombo Plan scholarship was given by developed Commonwealth countries to students from new Commonwealth countries to study abroad and return home to contribute to nation building.

“That was the duty instilled in us — get the opportunity to go abroad to study and come back and serve the country — and that was very important. Whatever you do is for the nation. We came back to serve the country in any way we could. I consider myself a pioneer in education in the arts and architecture,” he says.

Hijjas remains involved in architectural education as an occasional lecturer and external examiner at different universities. He sees this as a way of giving back to the country and society. He is now an adjunct professor at Universiti Malaya in Kuala Lumpur.

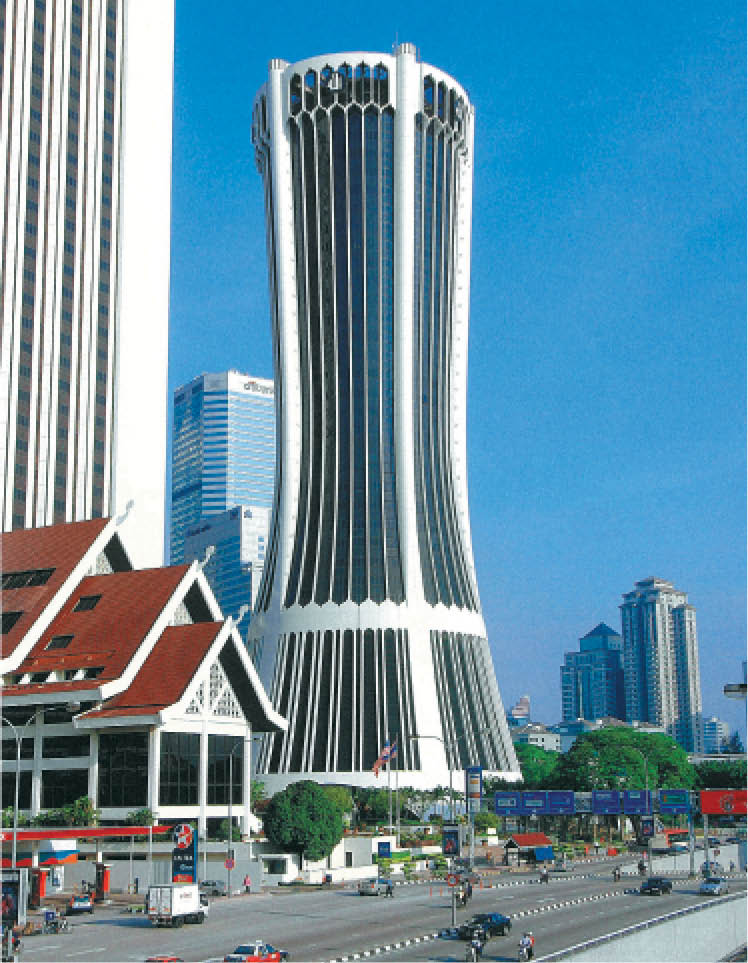

Hijjas Kasturi Associates has designed numerous iconic buildings in Malaysia, including Wisma Equity, the Embassy of Kuwait, Bangunan Tabung Haji, Menara MBPJ, Menara Maybank, the Securities Commission Malaysia building and Menara Telekom as well as Al-Faisal University in Saudi Arabia.

Hijjas Kasturi Associates has designed numerous iconic buildings in Malaysia, including Wisma Equity, the Embassy of Kuwait, Bangunan Tabung Haji, Menara MBPJ, Menara Maybank, the Securities Commission Malaysia building and Menara Telekom as well as Al-Faisal University in Saudi Arabia.

The firm designed the Malaysia Pavilion at Expo Milano 2015, themed “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life”. The design, in the form of seeds, emphasised better and more advanced sustainable food practices while celebrating the country’s rich food culture and gastronomical diversity.

Hijjas was always aware that what he designed would be left behind for future generations and he believes that buildings should have value. From the very beginning, it was important to him to create an architectural style that was recognised as Malaysian, that represented the newly independent, multiracial society that was Malaysia.

In a coffee table book published by Hijjas Kasturi Associates, Hijjas says Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, which he read as a third-year student, changed his attitude and his life.

He says that, to him, architecture is “real” and The Fountainhead taught him the value of real things. While buildings should meet certain requirements, he says, they should also add value — such as adding a cultural dimension.

The Malaysian identity

Hijjas’ search for a Malaysian architectural identity probably has to do with the fact that he was born when Malaya was still a British colony and he watched the struggle for independence. The new nation of Malaysia and its identity, post-independence, was embodied in a multiracial and multicultural society. Preserving the Malaysian identity and enhancing it to create a new architectural style was his philosophy.

Hijjas laments that most young people are not interested in preserving the culture today and many architects are now doing international designs — a style called “internationalism”. He believes the Malaysian architectural culture should be preserved, just as Malaysian food and languages are preserved.

“We always debate about why we want to put a Malaysian identity into our buildings. We can get buildings of modern design anywhere in the world — don’t we want Malaysian culture in our design? If we lose our culture, we lose everything, slowly, just like people in the West have lost theirs.”

Unexpectedly, the 80-year-old cites K-Pop (Korean Pop) as an example. He says Malaysians should take pride in their own culture and make it popular — as the South Koreans have done.

“It is like K-Pop, how the South Koreans have made their music popular. We should take pride in our own culture and make it popular and lucrative. For us, every race has its aesthetic value. We just need to pick it up, be innovative and recreate a new architectural design. Putting in some elements that reflect our culture wouldn’t cost a lot more but would contribute to a new architectural style that we can call our very own.”

Hijjas is definitely not one to follow the norm. His use of the words “innovation” and “new” throughout our interview is a characteristic that has made him who he is today.

When most people aspired to occupations such as teaching, medicine and law, his curiosity and his habit of breaking with the norm guided his footsteps to architecture.

“Back then, we were exposed to other occupations, but I knew I did not like all these things. I knew that I was good at art and I was curious about buildings because I helped my father build our own squatter house. I started reading about architecture when I was young,” he says.

“I was always doing something different. When my friends played football, I played tennis. There were tennis courts that nobody used, so I went there and played. I had no money to buy a racquet, so I bought it on six months’ instalments. When people joined the cadets, I joined the air cadets. I thought why do the same thing that hundreds of people were doing? I always wanted to try something different and not follow the crowd.”

The process of learning is constant, he adds, while the greatest teacher in life is observation. Things learnt from curiosity and observation later become part of one’s thinking process.

“If you are teachable, you can learn, even from a child. A child would say he does not know how to describe a building, but he would remember that the building [Menara Maybank] resembles a kris. It means it is simplicity that people remember. Theory has been taught and it gets better as you work, so, what is important is the expression. It is part of you, what you like, what you have learnt and absorbed. It is about intuition.”

Passion and love

Hijjas considers his profession “rewarding, challenging and blessed”. The rewards came when his designs won awards and he could earn a living while contributing to nation building.

Challenges included working in tough conditions and weather, when clients rejected his ideas and having a hard time collecting his fees.

“Sometimes we work until late into the night and complete [a design] but we do not get anything. It is part of life, so you have to like your job or else you can’t sustain it. Every building has its story and no two are the same. Some jobs are good, some are great fun and some are torture because of pressure from clients,” he recalls.

Hijjas hopes to continue to give back to society and pass on his experience and knowledge to the younger generation. His daughter, Serina Hijjas, is a director of Hijjas Kasturi Associates.

“I still teach whenever I can and a lot of people come to our place for practice. We also give out scholarships,” he says. “It is not about what we have or what restaurants we go to. Most importantly, it is what we can give back. To me, it is important to add to the treasure of the arts and architecture.”

This article first appeared in City & Country, a pullout of The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on Sept 19, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

8 Petaling

Bandar Baru Sri Petaling, Kuala Lumpur

Subang Hi-tech Industrial Park

Subang Jaya, Selangor

Sri Pinang, Bandar Puteri Puchong

Puchong, Selangor

Pusat Bandar Puchong

Bandar Puteri Puchong, Selangor

Taman Wawasan, Pusat Bandar Puchong

Puchong, Selangor

Taman Wawasan, Pusat Bandar Puchong

Puchong, Selangor

Taman Wawasan, Pusat Bandar Puchong

Puchong, Selangor