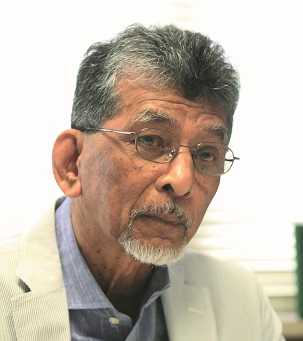

SAUNTERING across his office to retrieve his blazer, Datuk Hajeedar Abdul Majid points to photographs of his grandchildren displayed atop a long cabinet and chuckles fondly.

“Sometimes I wonder what the future holds for them,” he would later muse during the interview, saying that he is in the midst of writing a book to leave behind an account of history for future generations.

“Because without the past, there is no present. It is the past that determines our present state, so that we can plot for the future and hopefully, the future is better than the present and, definitely, the past.”

The principal architect of Hajeedar and Associates, Hajeedar served as the president of the Malaysian Institute of Architects (PAM) from 1985 to 1987, board member of the Board of Architects Malaysia from 1985 to 1997, and appointed member of the City Hall advisory board from 1985 to 1992. In 2012, he became the seventh recipient of the PAM Gold Medal, the highest honour awarded by the institute to Malaysian architects.

Born in 1945, Hajeedar began to have an interest in art during his early school days at Pasar Road Primary School in Kuala Lumpur. He would exchange his drawings with his late friend Lee Kong Kim.

“Drawing, like writing and talking, is a natural way of expressing myself. I would draw characters from comic books and Lee would draw characters like Wong Fei-hung. We even watched Wong Fei-hung movies in Pudu,” he reminisces.

Hajeedar’s talent was subsequently nurtured by his art teacher, the late Patrick Ng, in secondary school at Victoria Institution. A noted artist, Ng submitted Hajeedar’s painting for a United Nations’ World Refugee poster competition.

Hajeedar won the competition and his oil painting, Teluk Cempedak, was later exhibited at the National Art Gallery.

While he loved art, Hajeedar knew the inevitable struggles of an artist. “My parents encouraged me to do what I like, but every parent wants his child to be better than him, and my dad was a police officer. Also, I have always believed that nation-building is not a one-man mission but everyone’s responsibility,” he says.

After completing his sixth form, Hajeedar turned down both federal and state scholarships for foreign affairs and civil service education at Universiti Malaya, deciding instead to apply for a Mara scholarship to study naval architecture in the UK. In his application, he crossed out the word “naval”. “I was berated during the interview, but I explained my interest was to study architecture and not naval architecture. They didn’t think I would get a place in the UK … but I did.

After completing his sixth form, Hajeedar turned down both federal and state scholarships for foreign affairs and civil service education at Universiti Malaya, deciding instead to apply for a Mara scholarship to study naval architecture in the UK. In his application, he crossed out the word “naval”. “I was berated during the interview, but I explained my interest was to study architecture and not naval architecture. They didn’t think I would get a place in the UK … but I did.

“The sponsors agreed to grant me a one-year scholarship for my five-year course, and the subsequent years’ scholarship on the condition that I do well, and I did. When someone doubts you, you prove it to them that they were wrong … you don’t need to tell them,” he says.

After spending seven years studying and working in the UK, Hajeedar returned to Malaysia and served the Urban Development Authority for five years before setting up his own practice in 1978.

“When I started, we were still drawing with drawing boards and this,” he says, reaching for the drawing instruments on his desk. “I still keep them here as a reminder of the old technology.”

In 1984, his firm became the first local architectural office with full computer-aided design and drafting (CADD) capacity, says Hajeedar.

“The idea for computerisation for industrial usage, such as architecture and engineering, came about during my time in England. When I was with UDA and was sent for a city planning course in Japan, I had the chance to witness how computers could draw buildings and I predicted that the trend would reach our shores,” he recalls.

“When I got the job for Menara Bank Pembangunan (now known as Menara SME Bank), I got RM1 million of the RM3 million I was going to get for the job on lease from the client to buy the computer for my firm. Even the then prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad came to my office, a shoplot in Bangsar, to look at the computer. The CPU was as big as a fridge!”

Nonetheless, Hajeedar still encourages his architects to draw. “Think of the day when computers become obsolete. How will architects survive then?”

Some of his works include the MNI Twin Towers, Telekom Regional Office and Dataran Maybank. He has since completed 15 mosques, such as the Saidina Abu Bakar As Siddiq Mosque in Bangsar and National Mosque in the Republic of Maldives.

“Architecture is not meant for the architect, it is meant for the community. You don’t do it because of ego, but because there is a need for it,” says Hajeedar.

Let history remind us

Hajeedar has always believed in the need to conserve Malaysia’s heritage. “The architectural assets, or the tangible assets as I call them, serve as a reminder that we were once colonised.”

His first conservation and restorative work was the Industrial Court in Jalan Mahkamah. It was formerly the Chow Kit & Co Department Store.

“The late Tan Sri Harun Hashim, who was the president of the Industrial Court, read an article I wrote about the need to conserve our heritage. He called me and asked, ‘Can you put your money where your mouth is?’ He showed me the building to be turned into the Industrial Court,” says Hajeedar.

Subsequent conservation projects he worked on included the InfoKraft (National Textile Museum), the old Chartered Bank building (currently occupied by Jabatan Agama Islam Wilayah Persekutuan), the printing press building (now the Kuala Lumpur City Gallery) and Carcosa Seri Negara (previously the official residence of the first British High Commissioner in Malaya).

“We had five months to restore Carcosa and put it all together in time for [Queen Elizabeth II],” says Hajeedar.

Carcosa Seri Negara served as the temporary official residence for the queen during the 1989 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.

Hajeedar recounts that when he was 11, his father would bring him to Carcosa. “That’s where the negotiations for independence were done and my father was on duty,” he says. “When Tunku [Abdul Rahman] declared independence, I was at the stadium with my sister and father.

“And today, politicians are playing with the word pendatang (immigrant). I say respect the word pendatang because all of us are pendatang.

“My grandfather lives in Sumatra and it was my father who was a pendatang when he was 10. He crossed the Straits of Malacca to study in Kajang. The US is a country of immigrants with over 200 years of independence and we are only at 59, sudah gaduh,” he laments.

“So, remove the political boundaries and start with yourself and then get to know your heritage. As the Malay proverb goes, kalau tak kenal maka tak cinta,” says Hajeedar.

This article first appeared in City & Country, a pullout of The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on Sept 12, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Merdeka 118 @ Warisan Merdeka 118

Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur

Bangunan Setia 1

Damansara Heights, Kuala Lumpur

KL Gateway Residences

Bangsar South, Kuala Lumpur

Taman Nusari Bayu 1, Bandar Sri Sendayan

Seremban, Negeri Sembilan