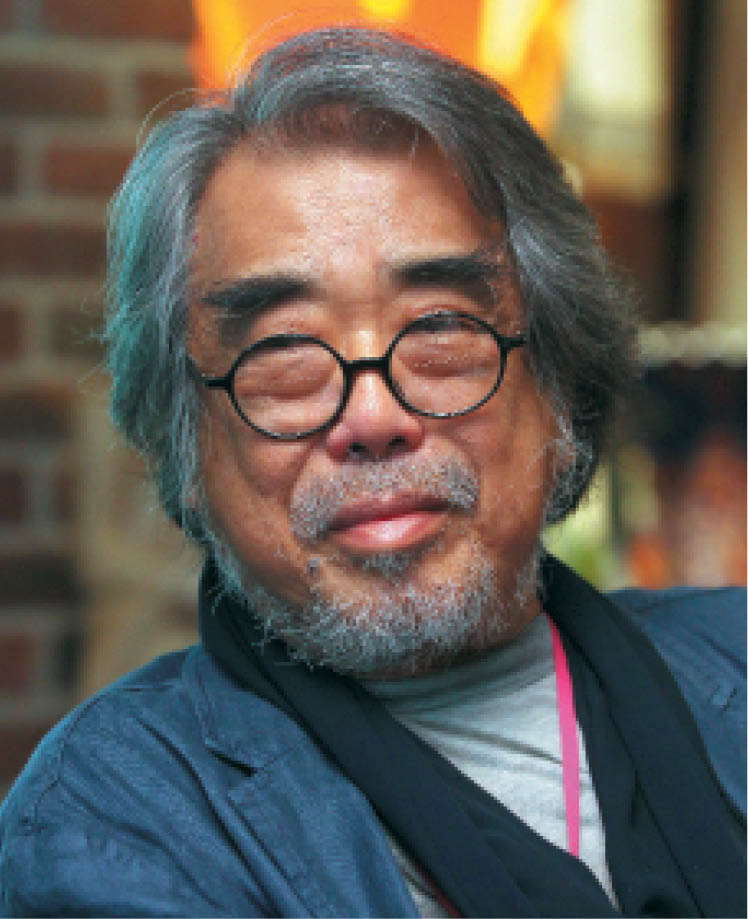

“You coming?” asks Professor Dr Jimmy Lim, founder and principal of Jimmy Lim Design, as he steps into his home office.

Though casually dressed in a denim dress shirt and sporting a scarf, Lim’s fiery disposition intimidates at first. But after a few minutes of talking to us, his expression softens.

“As an architect all these years, I have maintained my position, integrity and beliefs; I have not compromised them. And money is never a factor for me,” says Lim, 72.

Reflective and at times humorous, his demeanour suggests that he has seen it all.

“My philosophy of architecture is simple. I practise the architecture of humility, which involves culture, history, tradition, environment and people. Subsequently, I engage in the tai chi of architecture, which provides the solutions,” he says. “I am proud of our culture and traditions and I try to maintain honesty in my work.”

Lim specialises in tropical architecture, which involves ventilation shades and the use of natural materials.

He points to a brick wall in his office, saying, “If you look at this particular wall, its structure is called a load bearing wall [a wall that bears the weight of the entire building], where each brick can be seen and arranged carefully, unlike most reinforced concrete framed with brick infill that we can find in a lot of the buildings in Malaysia today. I try to maintain this kind of honesty, which is one of the reasons I think my work is different.”

Lim served as the president of the Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia (PAM) from 1991 to 1993. Regarded as one of the country’s top architects, he has designed bungalows, high-rise and low-rise commercial complexes, medical and sporting facilities, hotels and resorts. Lim was a senior architect and an associate of Project Architects Sdn Bhd from 1972 to 1977 before establishing his own practice — CSL Associates (now known as Jimmy Lim Design) in 1978.

His vast portfolio of prominent buildings includes Menara Prudential, Stella Maris, La Salle Sentul, Maran Tower, St John’s Institution in Kuala Lumpur, Awana Genting, Awana Resort Kijal and Awana Porto Malai, Langkawi. Lim designed Schnyder House in Kuala Lumpur (1986 to 1992), which consists of pavilions that are mostly free-standing on wooden pillars, a swimming pool and a roofed terrace. He also designed the T Y Chiew House, which won the PAM House Award in 1984. His designs have garnered awards from University NSW Alumni, Norway and the Commonwealth Association of Architects.

One of his notable works is the Salinger Residence in Selangor that won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Completed in 1992, this one-of-a-kind, 12,140 sq m traditional Malay house comprises two adjoining equilateral triangles, one for indoor living and the other for a veranda.

One of his notable works is the Salinger Residence in Selangor that won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Completed in 1992, this one-of-a-kind, 12,140 sq m traditional Malay house comprises two adjoining equilateral triangles, one for indoor living and the other for a veranda.

“I am proud of all the developments and projects I have done in the past. Each project produced the same amount of intensity and satisfaction. However, the Salinger Residence has got to be one of my proudest,” Lim says.

He describes the construction industry in the 1970s as fun and exhilarating. “When I first got involved in local architecture in the 1970s, it was a very exciting time. Kuala Lumpur was still very much a kampung, so to speak. Kampung Kerinchi still existed at the time. There were a lot of upcoming developments. My first project was a semiconductor plant for Motorola in Subang, and afterwards, I got involved in the Malaysian embassy project and several others in Kuala Lumpur before establishing my own firm, CSL Associates, in 1978,” he remarks.

“Compared to how it was back in the day, the construction industry in Malaysia has improved overall. The quality of our buildings has improved tremendously and we are now able to perform big-scale projects on a strict timeline.

“Attitudes have changed [to a certain extent]. The public is more conscious of the environment and is becoming house proud. When I first became an architect, there was greater emphasis on making buildings appear more Malaysian. However, I do find that local architecture is losing its Malaysian identity. At times, we forget that we live in a tropical climate, we forget that we have sun and rain, all the buildings are now made of glass and steel. Perhaps, it’s nobody’s fault, and it is what the clients want. Unfortunately, you have to abide by whatever the market wants in order to cari makan.”

An early start

Born in 1944, Lim grew up in Penang. “When I was about five or six years old, I used to follow my grandfather to junk shops, where we would buy a lot of things to renovate his house in Air Hitam. At the time, he wanted to extend the kitchen and so on. There was also a wooden bridge that had collapsed in the village. My grandfather undertook the task of building a concrete, stone bridge to replace it, and it is still standing today,” he says proudly.

“I remember thinking to myself, ‘this looks like fun’. And that was it, that did it for me. I began collecting old things, wooden windows and built houses from recycled materials in Penang.”

“At 15, I was sent to Sydney to further my studies at the University of New South Wales, and I stayed on for 13 years,” he recounts. “To be honest, I was not planning on coming back to Malaysia until I came across an advertisement at the university to design the National University of Singapore in Kent Ridge. It seemed like a good contract; they promised a house and a car, good salary and once the contract was renewed, they would send you back to Sydney for two months sabbatical. I later found out that I would be recruited across the Causeway when in fact, I was already based Down Under. So I turned down the job,” says Lim. “However, at the time, my mother was sending me all these newspaper cuttings of home, and that sparked something in me and I thought, ‘well, okay, let’s give it a go’.

“So, I moved back to Kuala Lumpur in 1972. It was good to return to Malaysia, to live in the tropics, to be able to experience Kuala Lumpur at an important time, to be able to eat my char kway teow, pau, popiah.

“My management philosophy is straightforward. I like to brief my team on the design and give them a free hand to achieve the best results. I also have quite a hands-on approach to design.”

He asserts that he has always been vocal about the construction industry, never shying away from expressing his opinions. “I got into a lot of trouble,” he recalls.

“I once represented PAM while speaking to the press in regard to the government’s plan to proceed with the KL monorail. At the time, people in the construction sector were up in arms, concerned about how the monorail would affect the heritage sites around the city. I felt I had expressed the concerns of many. And the next day, the newspaper headlines read, ‘KL Monorail, the white elephant, says PAM rep Jimmy Lim’. This caused a rift between PAM and Tan Sri Elyas Omar, who was the mayor (Datuk Bandar) at the time. PAM then issued an apology, stating that it was my opinion and not theirs. I thought that was perhaps the end of my career,” he laughs.

“I thought to myself, ‘life goes on’. I was still young at the time, so I continued to attend all the cocktail parties at the foreign embassies around town. And little by little, my profile began to rise as many applauded me for speaking up. And funnily enough, I finally met Tan Sri Elyas Omar and had a chat with him about it, and we realised that we had attended the same school. We are good friends until today.”

There were other scrapes with the authorities. “I also got into trouble once with Lembaga Arkitek Malaysia and the Singapore Institute of Architects for being involved in a MasterCard advertisement. I was accused of promoting my own company and it was described as disgraceful and infamous. This was unfortunate and definitely not the case. The advertisement was about featuring the masters of several professions, such as a violinist, botanist, architect and so on, so I thought it was good for the overall exposure of the industry,” Lim recalls.

“At the end of the day, the naysayers helped fortify my beliefs. They have made me a stronger person, so long as I maintain my honesty and truth.”

“One of the biggest challenges in the industry, by far, is maintaining my sanity,” Lim laughs.

“I have had to deal with really difficult clients and contractors who were always trying to find the easy way out. You really see people’s true colours and character in this field. It is a big lesson to learn and until today, I am still learning how to be diplomatic in dealing with them.”

Apart from his involvement with PAM, Lim was also a founding member and trustee of The Heritage of Malaysia Trust (Badan Warisan Malaysia) in 1983.

“I was active in Badan Warisan Malaysia. At the time, the Eastern Hotel was demolished, so we made a lot of noise. It was knocked down by Berjaya Group. With his influence, the mayor managed to get a contribution of RM200,000 from Berjaya and that was when the organisation started to collect money to help with conservation in the city.

“Today, I think there is a genuine attempt to do some conservation work in the city but there certainly has to be effort.

“Conservation is very important. There’s a saying, ‘today is yesterday’s tomorrow as today will be tomorrow’s yesterday’. It is important to have continuity and to move forward, you must always come back. It is important for the younger generation to recognise and keep these national treasures.”

Lim served as the president of the Friends of Heritage, Malaysia (Sahabat Warisan Malaysia) from 1989 to 1992.

Still going strong

Currently, Lim is working on a project in Johor. “I have got a commission to do a house for clients who are almost identical to those of the Salinger Residence — a couple who would like a holiday home,” he says.

“Details of the project are still confidential. It was difficult at first because I would like to achieve something that does not replicate the Salinger Residence due to the components. We have somehow achieved a design that has generic similarities but is different.

“The house is already under construction and will be completed next year, and if all goes well, I might even submit the design for the Aga Khan Award again. I find it satisfying to have my work recognised and to be included in publication.”

Lim was an adjunct professor at Curtin University, Western Australia, and the University of Tasmania, and an adviser to Alta College of Design in Malaysia. He was also the editor of Majalah Arkitek and has written for publications such as Berita Arkitek. He continues to lecture extensively at conferences and seminars.

“To me, the greatest thing about this profession is to build something of your own

creativity. To create something that is fulfilling to the clients and to be able to work consistently. To achieve something that is meaningful and that has relevance to your culture, heritage and environment.

“My advice to young, aspiring architects is to work hard. There is no shortcut to achieving success in this industry,” Lim says.

He comments that he does not need to find a way to relax. “I am already relaxed doing what I do, although it is nice to catch up with some old friends over drinks every now and then.”

When asked if he was planning on retiring any time soon, Lim says no, with a twinkle in his eye.

This article first appeared in City & Country, a pullout of The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on Sept 5, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Arte Solaris Mont Kiara

Mont Kiara, Kuala Lumpur

Pusat Bandar Puchong

Bandar Puteri Puchong, Selangor

Subang Hi-tech Industrial Park

Subang Jaya, Selangor

Sri Pinang, Bandar Puteri Puchong

Puchong, Selangor