“I LOOK at the ecological aspect of architecture. I’ve been doing it for 40 years and I’m still working on it with a simple objective in life — to invent something that will be eternally useful to the world and its people. It is basically my life’s agenda,” architect Datuk Dr Kenneth Yeang tells City & Country recently.

Born in 1948 in Penang, Yeang had his first taste of architecture when he was four years old, during a visit to the construction site of the house built by his father — a large, 2-storey modernist-style bungalow designed by Scandinavian architects Iverson, van Sitteren and Partners, who were based in Ipoh.

After his architecture training at the AA School of Architecture in London, he was one of the few who pursued a doctorate in ecological architecture and planning at Cambridge University.

“I started work on this in 1971, when I started writing my doctorate, which I finished in 1975. At that time, nobody was interested in ecological architecture and people thought I was a crazy hippie. It was not until the 1990s that people realised the importance of it,” says Yeang.

Today, he is regarded as the pioneer of ecological, bioclimatic skyscrapers. Yeang has been a director of T. R. Hamzah & Yeang Sdn Bhd since 1976, which currently has offices in China (North Hamzah-Yeang Architectural Engineering Design Company) and the UK (Ken Yeang Design International). He has authored over 12 books on green architecture and built a portfolio of over 200 projects worldwide.

In 2011, Yeang was awarded the Malaysian Institute of Architects (PAM) Gold Medal, in recognition of his lifetime achievement in Malaysian architecture, and has received the Merdeka Award, which recognises the recipient’s outstanding and lasting contributions to the nation and its people.

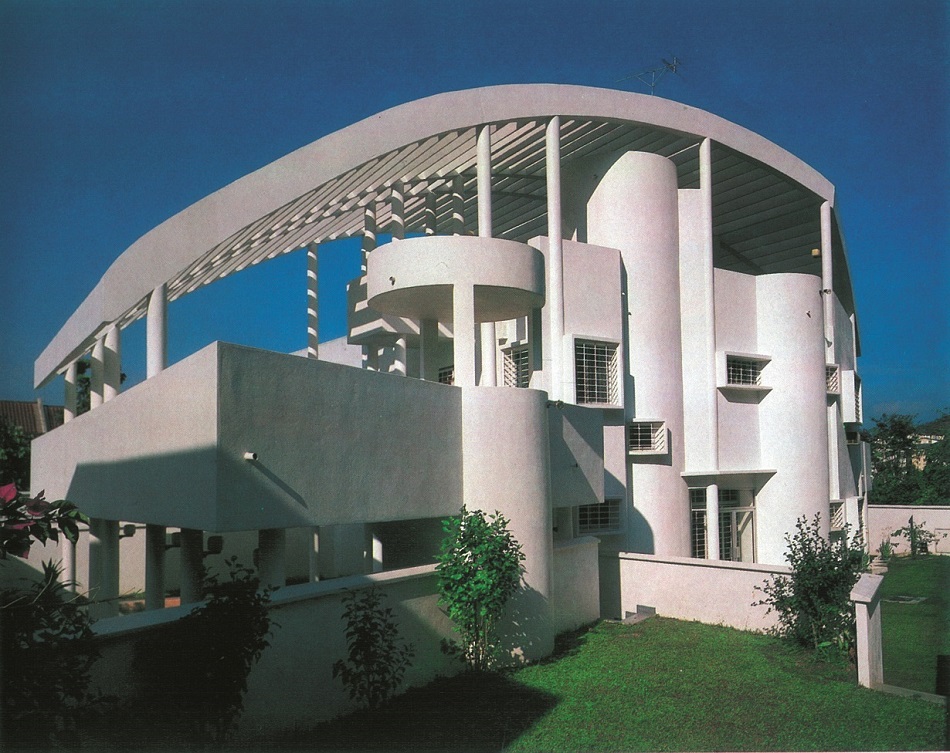

One of his earliest experimental prototypes in bioclimatic design that proved significant is the Roof-Roof House, Yeang’s residence in Ampang, Kuala Lumpur.

One of his earliest experimental prototypes in bioclimatic design that proved significant is the Roof-Roof House, Yeang’s residence in Ampang, Kuala Lumpur.

The Roof-Roof House was inspired by the common “umbrella” model, which acts as a cybernetic climate control device. With a perforated floor plan, all-round sliding glass doors are used to moderate the flow of wind through the house to cool the interior. And among the numerous experiments in the design is the use of wind-wing walls to direct wind into the interior.

“When the Roof-Roof House was completed in 1985, it was used against me by my fellow architects. Many of them ridiculed me for the unconventional design and asked clients to shun me as their architect,” laments Yeang. “But, of course, now these architects regard the house as being innovatively experimental,” he says.

Applying the same climate-responsive, passive-mode, low-energy design approach, Yeang has built over a dozen skyscrapers. Among his benchmark projects, Menara Mesiniaga at Subang Jaya, Selangor, was the prototype for bioclimatic skyscrapers in which the location of its services core contributes to the building’s passive-mode, low-energy design. The building was completed in 1992, and won the 1993 PAM Architecture Award for Excellence in Design for Commercial Buildings as well as the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995.

Another key project is Solaris at Fusionopolis, Singapore, a BCA Green Mark platinum project that was completed in 2011. “Solaris was a structure that expounded the idea of an ecological nexus via a continuous vegetation ramp that becomes a linear park in the sky,” explains Yeang. Solaris has received the PAM Gold Award in the overseas category and other awards.

Apart from developing the principles for an urban bioclimatic skyscraper, he has also explored integrating a set of eco-infrastructure as an approach to designing eco-master plans of cities, and has devised a “breathing” glass wall that lets wind through but keeps out the rain.

But even after achieving all of that, Yeang thinks there is still much to be done. “Green design is still very much in its infancy. In fact, I am personally concerned that I may not be able to achieve my agenda before I start pushing up daisies,” he says.

Guiding tenets for his design

Good design, for Yeang, must be immensely liveable, beautiful and aesthetically fulfilling, ultra green and ecologically benign; it must work and function well as a built environment, as well as meet local and international legislative criteria.

“I believe that the crucial consideration and responsibility of being an architect is that our design must create happiness and give immense pleasure to people. This is the incredible power and purpose of architecture,” he says.

Hence, he does not take to the current trend of creating iconic buildings simply to be unique. “In many instances, the forms are simply gratuitous. The uniqueness has got to be relevant to its time and place,” he remarks.

“The urbanity of a place must start with being a people-centric space, it must engender in people an awareness of who they are, where they are and the sense of time and reality they belong in. Each place has something special to give,” he adds.

The importance of focus

With a career spanning four decades, Yeang says the profession is not the same as it was when he first started, from the way work is delivered using technological advancements to the competitive business-like atmosphere.

“The increasing number of architects means an extremely competitive marketplace. You’ve got to be better than others. In Japanese, we call it Kaizen, which means continuous improvement. You have to continuously improve to catch up with those who don’t. The practice of architecture does not stay static and architects need to continuously learn,” says Yeang.

He adds that relationships also play a role in the business environment today. “For instance, there’s always someone who has an uncle in some government department who wants to give the work to his nephew. To compete with this sort of relationship can be very daunting.”

Nonetheless, Yeang thinks Malaysian architects and Malaysian architecture are as good as anywhere in the world. “There is a lot of talent, more talented than me. But the key to success is focus. Focus means to focus on one or two things and do them extremely well. If you’re going to do anything, do it extremely well,” he advises.

This article first appeared in City & Country, a pullout of The Edge Malaysia Weekly, on Aug 29, 2016. Subscribe here for your personal copy.

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Bandar Baru Sri Petaling

Bandar Baru Sri Petaling, Kuala Lumpur

Bandar Kinrara 5

Bandar Kinrara Puchong, Selangor

Iris Apartment, Taman Saujana Utama

Sungai Buloh, Selangor

Armanee Terrace 2

Damansara Perdana, Selangor

Pangsapuri Akasia, Bandar Setia Alam

Setia Alam/Alam Nusantara, Selangor