- Our concerns regarding the proposed URA are well founded and highlight critical legal and constitutional issues.

The Urban Renewal Act (URA) is set to be presented in Parliament next month. Among its contentious proposals is an 80% consent threshold for properties of 30 years old and a 75% threshold for properties over 30 years old. This means that a property could be compulsorily redeveloped even if 20% or 25% of owners oppose it.

This creates a situation where a minority of property owners may be forced to give up their property rights for redevelopment, potentially against their will. Since property rights are protected under Article 13 of the Federal Constitution (FC), the URA could be seen as undermining this right by allowing redevelopment without full consent, essentially forcing minority owners to comply with the majority decision.

Read also

Urban Renewal Act: draft Bill open for public feedback until March 7

Our concerns regarding the proposed URA are well founded and highlight critical legal and constitutional issues. Let’s break down the key points of how this law, with the reduced consent threshold, might contravene the constitutional protection in Article 13 of the FC and the principles of property rights, including those established under the National Land Code (NLC).

1. Article 13 of the FC: Right to property

- Protection against compulsory acquisition: Article 13 protects the right to property and mandates that no person shall be deprived of property except in accordance with the law, and with adequate compensation if acquisition is compulsory.

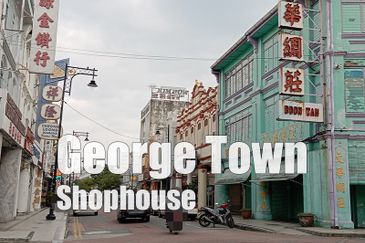

- Property rights beyond economic value: Property ownership isn’t just an economic asset; it has personal, emotional, and heritage value. By setting consent thresholds that could compel minority property owners to sell against their wishes, the URA risks infringing on this protected right.

- Majority rule vs individual rights: The URA’s consent threshold mechanism, by allowing a majority decision to enforce a redevelopment against the wishes of a minority, effectively deprives certain owners of their property rights without full consent. This could be argued as a violation of the individual protections that Article 13 intends to uphold.

2. Compulsory acquisition and adequate compensation

Under Article 13(2), any law providing for the compulsory acquisition of property must ensure adequate compensation.

The Supreme Court in Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Gombak vs Huat Heng (Lim Low & Sons) Sdn Bhd (1991) CLJ 16 held that the basic principle governing compensation is that the sum awarded should, as far as practicable, place the person in the same financial position as he would have been in had there been no question of his land being compulsorily acquired. This principle is known as the principle of equivalence. By this principle, the affected landowners and occupants are entitled to be compensated fairly for their loss.

While the URA might offer compensation to those who lose their properties through redevelopment, there may be a lack of legal safeguards to ensure the adequacy of such compensation, and the quantum of compensation could be disputed.

Additionally, the concept of "adequate compensation" in Malaysian law is often subjective and can be contentious. Property owners forced to sell under the URA might argue that the compensation provided does not fully reflect the property's market value or its emotional and personal significance. Compelling a minority property owner to sell his property at a price which he does not agree to or lower than fair market value is against the spirit of Article 13.

3. Indefeasibility of title under the NLC

- NLC principles and property rights: The NLC enshrines the principle of indefeasibility of title, meaning once a person has legal ownership, it is secure and cannot be challenged except under very specific conditions. This principle protects property rights, preventing arbitrary interference. The then Federal Court in P J T V Denson (M) Sdn Bhd & Ors vs Roxy (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd (1980) 2 MLJ 136 observed that the concept of indefeasibility of title is so deeply embedded in our land law that it seems almost trite to restate it.

- Potential erosion of security in ownership: A redevelopment law that permits forced acquisition by developer-majority consent would undermine this security, shaking public confidence in the durability of property ownership. If the URA allows majority interests, often driven by commercial profit, to override individual ownership, it will risk contradicting the indefeasibility principle under the NLC.

4. Public interest vs private-profit motive

- Compulsory acquisition for public purpose: Compulsory acquisitions pre-suppose that there is a clear and justified public purpose. However, the URA appears to prioritise developers’ interests — citing economic growth, but primarily benefitting private stakeholders — hence, its justification as a “public purpose” becomes questionable.

- Profit-motive concerns: When private developers influence the redevelopment process and push for thresholds that disregard minority objections, the Act may appear to serve the developers’ profit motives rather than genuine public needs. This could lead to legal challenges based on the lack of a valid public interest rationale.

5. Implications of circumventing constitutional and legal protections

- Risk of precedent: Enacting a law that permits circumvention of the constitutional protection on property could set a dangerous precedent. It suggests that property rights, long protected under Malaysian law, might be compromised for commercial interests.

- Erosion of public confidence in the legal system: Such a law could lead to diminished public trust in the government’s commitment to upholding property rights and the rule of law. Citizens might fear that any property could be subject to forced sale under similar redevelopment laws in the future.

- Judicial scrutiny: The judiciary may view this legislation as a misinterpretation or overreach of legislative power if it infringes upon constitutional rights and established land law principles. The courts could demand stricter thresholds or potentially strike down provisions that they find unconstitutional.

6. Balancing development and property rights

- Legitimate urban renewal vs forced dispossession: Urban conservation and urban revitalisation, as opposed to urban reconstruction, can play a valid role in addressing urban decay and supporting sustainable development. However, the URA is susceptible to abuse and if the URA is implemented in a way that leans too heavily in favour of developers’ interests over homeowners' rights, it will risk undermining legitimate urban renewal efforts. Buildings could be demolished purportedly for redevelopment, even when they are far from reaching the end of their structural lifespans. Most experts estimate that a typical building is designed to last anywhere between 50 and 60 years before extensive maintenance or preservation work are necessary to keep the property safe.

- Government accountability and transparency: Ensuring transparency and engaging with stakeholders, including homeowner groups, will be essential to avoid the perception that the government is catering solely to developer interests.

Conclusion

While the URA aims to facilitate urban redevelopment, it does face potential legal challenges because of its implications on property rights under Article 13.

In short, while urban redevelopment can drive economic growth, it should not come at the expense of citizens' constitutional rights.

This article is written jointly by Datuk Chang Kim Loong, honorary secretary-general of the National House Buyers Association (HBA), and Koh Kean Kang, HBA legal advisor.

HBA is a voluntary non-government and not-for-profit organisation manned wholly by volunteers.

HBA can be contacted at:

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.hba.org.my

Tel: +6012 334 5676

The views expressed are the writers’ and do not necessarily reflect EdgeProp’s.

EdgeProp.my is currently on the lookout for writers and contributors to join our team expansion. Please feel free to send your CV to [email protected].

Looking to buy a home? Sign up for EdgeProp START and get exclusive rewards and vouchers for ANY home purchase in Malaysia (primary or subsale)!

TOP PICKS BY EDGEPROP

Sendayan Merchant Square

Seremban, Negeri Sembilan

Taman Bukit Indah @ Iskandar Puteri

Johor Bahru, Johor

Seasons Luxury Apartments @ Amara Larkin

Johor Bahru, Johor

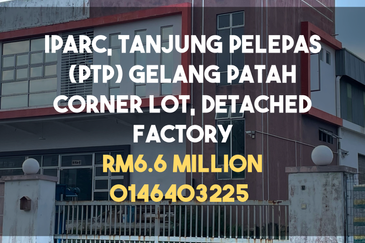

i-Parc @ Tanjung Pelepas

Gelang Patah, Johor