- To sustain the infrastructure investment level in the face of reductions in the central government capital grants, countries need to embrace the idea of sub-national entities accessing private finance for investments in public infrastructure and services.

- A paradigm shift from the grant-based resource mobilisation approach to the market-based financing instrument that seeks to close the local infrastructure-financing gap should seriously be looked into.

Economic growth and urbanisation are positively linked. Cities are the driving force for economic development, while economic growth further stimulates a higher level of urbanisation. A higher concentration of urban population not only generates more interactions, exchanges and business opportunities, but also promotes creative thinking, knowledge spillovers, new ideas and technology developments, leading to a higher economy of scale and wealth agglomeration.

No country can sustain economic growth without the growth of cities, as cities not only demonstrate a higher economic growth than their rural counterparts, but also generate a higher gross domestic product (GDP) than their respective population share. For instance, Tokyo, with 26.8% of the national population, produces 34.1% of the country’s GDP; while London’s 20.3% national population accounts for 25.4% of the national GDP.

The role of cities in national economies is even more significant among developing countries. In Shanghai, Manila, Cape Town, Karachi and Nairobi, cities can generate more than 100% higher GDP than their population share; while in cities like Yangon, Chittagong, Kuala Lumpur and Mumbai, more than 200% higher GDP than their population share can be generated (Figure 1).

However, this does not mean cities in developing countries are much more productive than the ones in developed countries. A measure of productivity by GDP per capita shows that cities in developed countries generally record higher levels than the ones in developing countries. This indicates that the productivity gap and inequality of development between cities and rural areas are much larger in developing countries than in developed countries, which is further evidence of the link between economic wealth and cities.

Since cities possess huge untapped economic potential that can be leveraged to create wealth and economic opportunities, investment in high quality urban infrastructure to support urban compactness, integration and connectivity is desperately needed. However, even the best urban plans risk ending up unused if they are not accompanied by financial strategies for implementation.

Currently, cities are under-resourced to fulfil their potential as drivers of national economic development and prosperity. This is because rapid economic development, urbanisation and population growth in cities have resulted in an ever-widening gap between current spending and finances required to meet the increasing demand for infrastructure.

Municipal governments often lack financial means to address the vast challenges facing them. For example, of the total government revenues in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, the central or federal government receives 52.6%; provincial or state government receives 19.5%; and municipal or local government receives 10.2% (Figure 2). Municipal governments in most countries have less than a quarter of total government revenue. In some countries like Slovakia, Costa Rica, Lithuania and Greece, municipal governments are even allocated less than 5% of the government revenues.

Most cities, especially in developing countries, depend heavily on central government transfers, with lesser revenue derived from property taxation and service charges. More lucrative sources of revenue potentially suitable for financing urban areas, such as income taxes, sales taxes and business taxes, continue to be controlled by the central governments. While local authorities are able to derive revenue from property taxes and service charges; meaningful tax increases are sometimes refused or delayed by central governments for fear of eroding political support from the urban population; or even rejected by the local authorities themselves for fear of political backlash from local taxpayers. Consequently, there are huge vertical imbalances at the sub-national level in terms of sharing responsibilities and available fiscal resources.

Financial limitations of state governments in Malaysia

Similarly, in the case of Malaysia, contrasting budget and development revenue reveal the imbalance between federal and state governments. The federal government has legal authority to impose income and sales taxes. But state governments can only rely on land-related transactions, fees on small-ticket items like hawker licences for independent revenue, and fiscal allocations from the federal government. Besides, state governments are banned from borrowing to finance development projects, which means they are unable to raise revenue to build the infrastructure needed to clear production bottlenecks in local industries.

For example, the Penang state government was reported to collect a total of RM147.27 million for development revenue in 2022, a decrease of 44% compared with RM263.41 million reported in 2021 (Figure 3). Transfer from the state’s operating expenditure remained the main source of income for development projects, representing 89% of the total development income; while federal loans and grants have been declining from RM71.42 million in 2000 to RM15.52 million in 2022.

In the city level — KL for example — the federal government’s grant for the KL City Hall (DBKL)’s development budget in 2024 saw a 25% drop from RM103 million in 2023 to RM77 million in 2024.

A shortfall in municipal budgets could result in a wider range of financing options to bridge the city’s infrastructure needs; which then leads to the underinvestment in infrastructure that would further slow down the economy and subject the society and businesses to higher levels of pecuniary and environmental stress.

To sustain the infrastructure investment level in the face of reductions in the central government capital grants, countries need to embrace the idea of sub-national entities accessing private finance for investments in public infrastructure and services. In other words, a paradigm shift from the grant-based resource mobilisation approach to the market-based financing instrument that seeks to close the local infrastructure-financing gap, should seriously be looked into.

Expand funding pool by tapping private individual and institutional savings

Notably, local governments in most countries have had access to credit facilities which are available through government sponsored lending programmes and bank lending. These funds, however, may be restricted to the development of local amenities and the provision of welfare to the public. The challenge is to expand the “market-based” funding pool for local governments by tapping private individual and institutional savings.

Municipal bonds are considered as one of the innovative external sources of financing to meet the sub-national or local government financing challenges. It is a debt security issued by a state, municipality or county to finance its capital expenditure. Since municipal bonds are often exempt from most taxes, they are an attractive investment option for individuals in high tax brackets.

Municipal bonds are different from those issued by corporations, despite both being fixed income investment products. First, it is mandatory that the proceeds of the municipal bonds’ issuance be used to finance the project or activity that will generate revenue or give benefit to the public, which is not the case for corporate bonds issuance where it can be used for working capital, investment or refinancing purposes.

Second, the issuance of municipal bonds needs a regulation issued by the local government to ensure the commitment to repay the municipal bonds should there be a change of the head of local government before the maturity date. Third, the issuance of municipal bonds needs the approval from the Ministry of Finance to ensure that the local government that will issue the municipal bonds has the capacity and capability to manage the bonds until its maturity date.

Developing countries actively promoting municipal bond market

Many countries are attempting to accelerate the development of markets in long-term bonds sold by local governments and local government-owned enterprises. For example, developing countries in Asia and South America are particularly active in promoting municipal bond market development, while other countries in various forms of social and economic transition, such as South Africa and former Soviet block nations, have also begun to recognise the potential usefulness of municipal markets.

While sub-national governments of Western Europe hold a long-standing record of harnessing long-tenor market capital for urban infrastructure, the adopted models are slightly different, where they are either developing their home-grown development banks, or the so-called private financing initiatives (PFIs), in which the government contracts with the private sector to deliver specific infrastructure investments and services.

The US municipal bond market suggests to other countries that municipal bonds can offer a way of helping local governments, particularly urban governments which finance critically needed infrastructure with domestic private capital, rather than through sovereign borrowing by national governments. To note, nearly two thirds of the cities’ infrastructure and urban development in the US are financed by municipal bonds; and there are approximately 50,000 issuers of municipal bonds, including states, in the US.

Malaysia’s experience: the Pasir Gudang PPP Municipal Sukuk

Sukuk is the Arabic name for a bond-like instrument that complies with shariah or Islamic law, which forbids speculation and the payment or receipt of interest on loans. While sukuk operate similarly to conventional bonds, they stand apart in their structure and method of generating returns (Table 1). Unlike typical debt instruments, sukuk represents ownership stakes in underlying assets, which can be tangible (such as real estate or operating assets) or intangible (like goodwill or copyrights). Their returns are derived from profit-sharing arrangements based on the underlying assets, further setting them apart from typical debt instruments.

Sukuk issuance has opened up potential sources of funding for municipal infrastructure projects requiring large capital outlays with long construction and amortisation periods. Malaysia's first and only experience in municipal bonds is through the issuance of Pasir Gudang PPP (public-private partnership) Municipal Sukuk by the Johor state government in 2005. More specifically, it is a mudharabah bond issued by PG Municipal Assets Bhd, which is a profit-sharing arrangement backed by tax assessments for industrial properties collected by the Pasir Gudang local government authority.

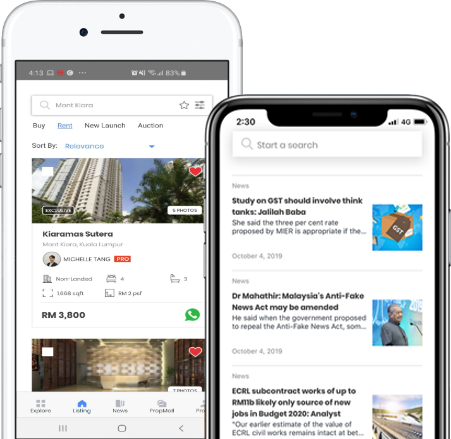

In 2005, the municipality of Pasir Gudang issued a RM80 million sukuk to beautify the city and urban regeneration. Instead of leasing public property to generate funds, the municipality innovatively used the tax revenue stream as the underlying asset for the mudarabah sukuk. The asset was derived from proceeds from management and collection of property tax of industrial property in Pasir Gudang. Profit from tax collection was shared according to an agreed ratio between partners. The maturity of the sukuk was one to six years with each six tranches of the sukuk mudarabah to be refunded at the end of each respective investment period.

There were two parallel mudarabah arrangements between the public sector agencies, investors and entrepreneurs in the structure of a PPP. The issuer or Special-Purpose Vehicle (SPV) was the PG Municipal Assets Bhd (PGMAM). The SPV first entered into a mudarabah contract with sukuk holders (investors), whereby the investors contributed RM80 million as capital, which determined the investor shares and rights proportionate to their capital contribution in the mudarabah contract. Under the second mudarabah contract, the SPV invested the entire capital of RM80 million in the Pasir Gudang local authority as the project manager (mudarib).

Profits were expected as the local authorities of Pasir Gudang started using the mudarabah capital in managing the collection of property taxes. The rabbul mal (investors) agreed to forgo amounts in excess of agreed profit-sharing amounts. The profits from the property taxes were then channelled to the SPV which distributed the profit share amongst the investors as per the agreed profit rate. Figure 4 illustrates a simple structure of sukuk mudarabah.

When PGMAM issued its “municipal bonds” in 2005, it became an original in two significant aspects. First, it was the first Malaysian municipality to tap the bond market. Second, it opted to do so under an Islamic mudarabah partnership contract. Leveraging its property taxes to raise the paper, the Pasir Gudang municipality received an AAA rating from Rating Agency Malaysia Bhd (RAM), which was subsequently reaffirmed throughout the tenure of the paper.

Challenges faced by municipalities in bond issuance

While PGMAM broke new ground in paving the way for municipal councils to raise funds, the fund-raising precedent has not been followed by other local councils since the sole issuance of municipal sukuk in 2005. The limited issuance of municipal bonds or sukuk has to do with the common factors that hinder cities and local municipal infrastructure investment financing instruments: restrictions on government entities raising funds independently.

Even where laws authorising municipal bonds or sukuk exist, the process of approval of provincial proposals for projects and financing can be cumbersome. The Pasir Gudang Municipal was an exception as it is the first local authority in Malaysia that was privatised, and the entire municipality itself is owned by Johor Corporation, the investment arm of the Johor government.

Besides, specialised laws and regulations that govern municipal sukuk make it a lengthy process. Though this is intended to eliminate technically unsound projects, this often undermines local decision in investments projects. Being complex in nature on both the regulatory and shariah fronts, preparation for sukuk issuance needs to cover all technical aspects characterising all phases of the implementation. Thus, local authorities need the capacity to develop a more self-financing mechanism to design, launch, and successfully implement sukuk. This is evidenced, where according to Malaysia’s DanaInfra Nasional Bhd, out of the country’s annual infrastructure investment needs of approximately US$180 billion (RM835 billion), total annual infrastructure sukuk issuances has been less than US$30 billion per annum.

Despite the need to identify underlying assets, the sovereign sukuk market has always been contingent on the financial situation of the originator, where in the case of municipal bond issuance: the municipality. Investors could be reluctant to invest in municipal bonds as they could be exposed to construction risks like construction delays or overrun costs.

For private capital to invest and the private sector to participate in the development of public infrastructure, municipalities must first demonstrate that they are creditworthy: be it the ability to efficiently collect and maximise their capacity for taxes and assessments, or the capacity to prepare capital budgets and evaluate long-term financing plans. Only when practical arrangements for strengthening the security behind municipal borrowings are put in place, the private sector lending to the local governments can grow.

Potential for Malaysian municipal bonds/sukuk issuance

Malaysia has gone through extensive experiences in using Islamic financial instruments to support infrastructure development, with the fact that a majority of the world’s infrastructure sukuk is being issued out in Malaysia. Since 1990, when the first corporate sukuk were issued in Malaysia by Shell MDS, worth RM125 million, the sukuk market in Malaysia continues to thrive while supported by the country’s conducive issuance environment, facilitative policies for investment activities, and comprehensive Islamic financial infrastructure.

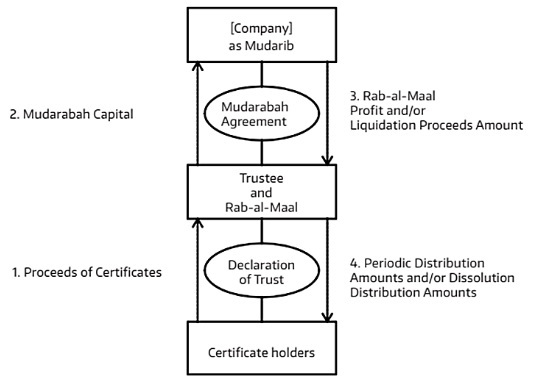

This is evident as Malaysia continues to spearhead the international sukuk market, commanding 40.3% market share of global sukuk outstanding and 43.3% share of global sukuk issued in 2022, making it one of the largest sukuk markets in Asia (Figure 5). To note, global sukuk outstanding was recorded at US$751.6 billion as of 2022, despite lower issuances (US$175.9 billion) during the year amid global tightening of monetary policy (Figure 6).

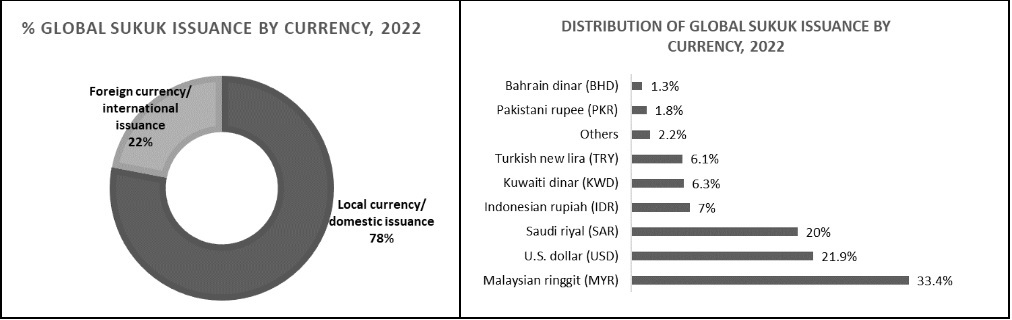

The Islamic sukuk market in Malaysia provides customised solutions to sovereign and corporate issuers through a variety of sukuk structures using different Islamic contracts such as Ijarah (leasing), Murabahah (mark-up scale), Musharakah (joint venture), Wakalah (agency), or hybrid structures based on combinations of shariah contracts. Although the Malaysian sukuk are predominantly issued in local currency on the domestic market, they have gained a reputation for being dynamic and flexible. This calls for an increasing number of foreign investors, both Muslims and non-Muslims, to capitalise on the strength of Malaysia’s Islamic capital market to issue regular short-term commercial papers to meet their ongoing financing needs. To note, the domestic issuance forms 78% of the total sukuk issued globally in 2022, and about one third of the sukuk issuance was in the Malaysian ringgit (Figure 7).

Besides, sukuk are backed by real economic activities, which enable them to tap a wider investor base from both the Islamic and conventional spectrum. With its focus on financing the productive economy based on underlying real assets and a set of principles that are closely aligned with the principles of ethical and responsible finance, sukuk are well positioned to help mobilise long-term capital in emerging and developing markets, thereby exerting greater influence on achieving a balanced socio-economic development.

Most importantly, sukuk, to some extent, resembles the PPP financing, whereby investors finance the assets, own them — leading to true securitisation — and then transfer them back to the government at maturity. However, they are viewed as a less expensive way of financing infrastructure than by PPP or methods that maintain greater public control over projects and service provision, due to their distinctive features such as risk sharing and asset-based requirements that support PPP while ensuring the sustainability of infrastructure projects.

In this sense, sukuk can be deployed by municipalities with a proven track record for a range of objectives to help deepen the pool of capital to finance investments and support growth. With the establishment of a mature sukuk market in the country, this will certainly provide a solid foundation for confidence in the Malaysian municipal bond market.

Decentralisation in line with SDG

With rapid urbanisation, governments can no longer continue paying for public investments by raising taxes or borrowing from local and international markets. Fiscal decentralisation — which entails shifting some responsibilities for expenditures and/or revenues to lower levels of government — has, thus, become a mainstream alternative framework for fiscal policy in many countries.

Decentralisation of borrowing authorities to sub-state levels and city councils will not only promote transparency, independence, and self-discipline in sustaining operations; but is also in line with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs) for government finance. Hence, the viability of local authorities fulfilling their own funding needs requires deeper consideration. If strong institutions, good governance, and a supportive legal and regulatory framework are in place, fiscal decentralisation can support and enhance municipal finance.

As shown in the case study — Pasir Gudang PPP Municipal Sukuk — the deployment of municipal bonds/sukuk in Malaysia is possible, but it would require the federal government and municipalities to develop capabilities and expertise in partnership with other stakeholders. Municipal finance inevitably requires special laws or regulations detailing the scope of budgeting and decision-making powers at the local level. Therefore, operational autonomy achieved through fiscal and political decentralisation needs to be integrated into municipal governance structures and management approaches. Besides, a great deal of preparation is needed for municipal bonds/sukuk issuance, much like a PPP project. Given the concerns over possible delays, overruns and risks in infrastructure projects, the federal government should support and guarantee municipal bonds/sukuk.

Dr Foo Chee Hung is MKH Bhd manager of product research and development.

Looking to buy a home? Sign up for EdgeProp START and get exclusive rewards and vouchers for ANY home purchase in Malaysia (primary or subsale)!