How much do you think your car park space is worth? How much do you think it costs to build? Car park space has been deemed an essential facility for any type of building or development in Malaysia.

According to property developer MKH Bhd, a car park facility can contribute to the price of the property, and could be one of the many factors hindering homeownership in the country.

Besides the usual supply and demand, as well as the developer’s profit margin, house prices are determined by the cost of construction, including the construction of the parking spaces in a development. Hence, the cost of the car park space will have an impact on the final pricing or the affordability of a property.

But how much does a car park space cost developers? How much does it contribute to the selling price of a property?

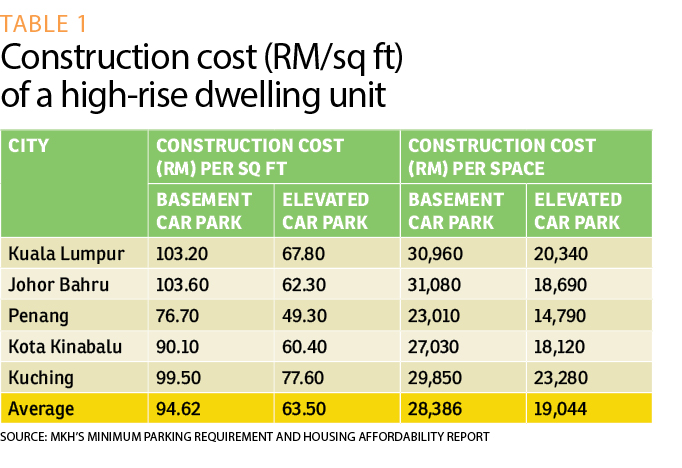

In a research report on “Minimum Parking Requirements and Housing Affordability” completed in June 2018 by MKH, it was found that in the country’s capital cities of Kuala Lumpur, Johor Bahru, Penang, Kota Kinabalu and Kuching, the construction cost of a 300 sq ft basement car park averaged RM28,386 while an elevated car park of the same size costs RM19,044.

The amount was calculated based on the required gross built-up area of 300 sq ft for one car park and the estimated average construction cost of RM94.62 psf and RM63.48 psf for basement and elevated car parks respectively in the five cities as stipulated in the JUBM & Arcadis Construction Cost Handbook Malaysia 2017. The JUBM & Arcadis Construction Cost Handbook Malaysia 2017 was a report compiled by quantity surveying firms JUBM Sdn Bhd, Arcadis (M) Sdn Bhd, Arcadis Projeks Sdn Bhd and Arcadis Consultancy Sdn Bhd.

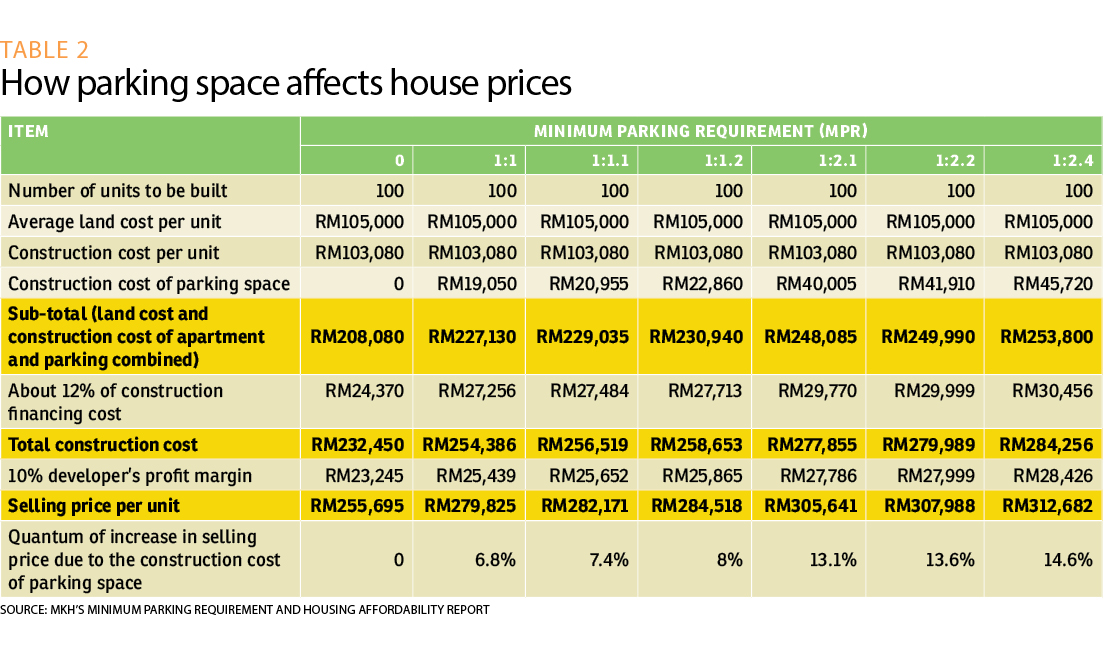

It shows that the more parking spaces are allocated in a housing project, the higher the residential unit price will be, as the developer needs to fork out more capital for the car park bays and thus incurs higher construction costs.

Developers have to follow the Minimum Parking Requirements (MPR) determined by local councils which states the minimum provision of car park bays for each dwelling unit and the extra parking space for visitors. However, the MPR differs for each project and circumstances.

For instance, some high-rise residential developments have an allocation ratio of 1:2.4 which means they are required to allocate two car park lots for each dwelling unit and 20% of total car park bays for visitors.

In this case, the developer will need to allocate a total of 720 sq ft in parking spaces —two residential car park bays of 300 sq ft each plus 20% of the total size of the two car park bays— to be allocated for visitors. This means construction cost of the parking space for the unit in this case will go up to RM45,720 assuming that this is an elevated car park and the estimated average construction cost is RM63.50 psf.

Different types of projects have different sets of MPR, such as 1:1, 1:1.1, 1:1.2, 1:2.1 and 1:2.2.

However, this has become an issue of contention for developers, especially for those involved in affordable housing developments as the unit prices for these developments are capped while the MPR still has to be strictly adhered to.

How does the MPR impact house prices?

Assuming a developer has bought a 1.3-acre land at RM10.5 million and wishes to construct 100 standard apartment units with a construction cost of RM103,080 per unit, to provide elevated parking space for the residents, the apartment unit price will vary under different MPR as shown in Table 2.

“While these figures may vary when taking into consideration the land cost, construction financing, developer’s profit margin and other additional costs, [the MPR] significantly reduces a developer’s incentive to produce affordable housing,” says MKH managing director Tan Sri Eddy Chen.

The developer opines that one of the biggest issues about the MPR is that it wastes a great deal of space by applying a “one size fits all” solution to a complex and evolving situation.

Hence, he urges the local authorities, which regulate MPR in their jurisdictions, to study the possibility of reducing the number of parking under the MPR to a more reasonable level according to demographic, geographic and management factors.

For instance, the MPR can be reduced for low-cost housing where car-ownership is lower.

Citing the Household Income and Basic Amenities Survey 2016 done by the Department of Statistics Malaysia, Chen says the car-ownership of the B40 group only stood at 67% in 2016 while the M40 and T20 groups recorded a rate of 95% and 100%, respectively.

“When parking is bundled, car-free households cross-subsidise the parking of their neighbours. And since car ownership of lower-income households tend to be lower, it is unfair for them to pay for parking they do not need,” says MKH in the report.

TOD, the way forward?

Chen, who is also chairman of the 1Malaysia People’s Housing Programme or PR1MA, believes that transit-oriented developments (TOD) should be made the intrinsic concept in planning practices as the TOD concept could tackle challenges of urbanisation such as rising private vehicle ownership, the urban sprawl and traffic congestion.

TOD’s positive implications on environmental quality, climate change mitigation and human physical wellbeing have been well-documented, adds Chen.

“If we believe housing affordability can be enhanced through the reduction or abolition of stringent parking requirements, then TOD is a compatible development strategy that would help society shift towards a lifestyle that is less dependent on private cars,” he says.

Furthermore, he opines, as density rises, more people will choose to move around the city by public transit while fewer cars are used.

According to the TOD Database, a database created by the Center for Transit-Oriented Development (CTOD), doubling the residential density is associated with a 19.7% increase in the modal share of public transport and a decrease of 0.4 vehicles per household,

Chen says the findings of MKH’s study on MPR have been shared with organisations such as the Real Estate and Housing Developers’ Association (Rehda) and a few local authorities.

“The issue of MPR has been frequently raised by Rehda. The importance of this study is to provide evidence on how MPR affects housing affordability so that more emphasis and support from the government can be given to TOD especially in highly urbanised and densely populated areas such as the Klang Valley which has seen improved and more efficient public transport network,” offers the former Rehda president.

The government, he says, should consider expanding the TOD radius, from 400m to 750m; or to justify a TOD project based on the walking period (i.e. 15 minutes) so that more adjacent developments can benefit from the 1:1 parking requirement as applied to current TOD projects.

“This not only helps to achieve the ultimate goal of enhancing housing affordability, but also increases the liveability of urban dwellers in highly urbanised regions,” says Chen.

He also cites findings from a report by the Asian Development Bank on Parking Policy in Asian Cities as follows:

• The Western experience suggests the conventional approach, which depends on MPR, is problematic and is especially poorly suited to a dense urban fabric (which accounts for much of urban Asia).

• Japan has a unique set of policies that has resulted in a market-oriented parking system with ubiquitous commercial market priced parking. This was a result of three pragmatic policies: minimum parking requirements that are set very low and which exempt small buildings, very limited on-street parking and a proof-of-parking rule (which requires access to a night-time parking place to be secured before registering a car).

• Hong Kong, Seoul and Singapore use MPR despite being known for their transport demand management policies. However, they show some signs of shifts away from the conventional approach. “They have been making their parking requirements more moderate. Each has elements of constraint-focused parking management in transit-rich locations. There are signs of market-oriented parking supply, especially in Hong Kong.

“As urban spaces become ever more crowded, growing urban populations are demanding more living space and MPR has led to the creation of excess, poorly-distributed and under-utilised parking facilities.

“This not only discourages housing development but also encourages vehicle ownership, causing high costs in terms of resources consumed and distortions to development patterns,” stated the report.

This story first appeared in the EdgeProp.my pullout on Nov 2, 2018. You can access back issues here.